Despite rapidly evolving maritime threats, exposure to serious combat this year, and bold rhetoric about robotic sea systems, the U.S. Navy is often touted as the least innovative and least tech-forward service. Last week at Sea Air Space, Saildrone and Thales announced a new submarine-hunting partnership, Anduril unveiled a new UUV (aka torpedo) family, and Saronic demoed its speedboat Corsair despite wind and chop in the harbor. Witnessing these hard-charging tech displays from industry, Navy admirals said little about their vision to adopt the tech.

The Navy is often slandered as one of the least innovative and slowest moving branches of the DoD. Is this a fair characterization?

Today, we, Austin Gray, a former Navy officer and co-founder of Blue Water Autonomy, and Maggie Gray, a venture capital investor at Shield Capital (no relation), have teamed up to examine this exact question. If you like contracting data, and analyzing a problem statement from multiple angles, this post is for you.

Our goal: unpack whether the Navy really is hard to sell to and what startups and the Navy can do to better foster maritime innovation. As a VC-investor and a startup founder, we’re looking at this from our own lens. Can startups successfully navigate the Navy, build the products sailors need, and successfully compete for Navy contracts?

First, we’ll look at some hard numbers that illustrate how hard it is for new entrants to work with and sell to the U.S. Navy. This problem statement isn’t an easy one to quantify, so we looked at it from a few angles.

Early adopter: How many companies get their first AI / ML or autonomous systems related contract with the Navy, vs another service? What about their first five?

Force Structure: Do lots of ships, aircraft, and submarines make the Navy tough to work with?

Startup-Friendly Contracts: SBIRs, OTAs, fixed cost contracts, and simple contract vehicles offer startups a chance to compete – how does the Navy use these tools relative to other services?

Navy Program Offices: How to quantify whether a program office is incentivizing competition, or favoring incumbents?

These numbers will paint an ugly picture: Navy buys lots of complex technology from incumbents, and it’s hard for startups to compete. After framing this problem, we’ll discuss potential solutions for companies, investors, and the government. We’ll also call out a few innovative pockets within the Navy that should serve as a model for how the rest of the Navy should work to improve the state of innovation.

Much of the contracting and budget data we analyze here is from Obviant (huge shout out to the awesome Obviant team for helping us with our many data requests).

Current State of Navy Technology Spending

Today the Navy still has a hardware centric mindset. It invests heavily in large, legacy hardware platforms like aircraft carriers and submarines built by traditional defense primes and underinvests in new software. For instance, many Navy ships still run Windows XP, an operating system released in 2001 and discontinued in 2014.

There is a significant gap between venture capital (VC) funding for DoD focused startups and actual DoD spending on startups’ technology. While investors have deployed more than $100B in defense-focused startups since 2021, VC-backed startups still win few DoD contracts. Palantir and Anduril have just over $1B each in US government revenue, compared with Lockheed Martin’s $70B+, General Dynamics $47B+, and Northrop Grumman’s $40B+.

Consider an even smaller subsection of DoD-focused startups specifically targeting the Navy. Just 8 startups building autonomous naval vessels have raised more than $1.3B total. But in its FY25 budget, the Navy requested just $172.2M for unmanned surface vessels and $191.5M for unmanned underwater vessels. In contrast, the Navy requested $36B for shipbuilding, $16.2B for new aircraft, and $6.6B for new weapons.

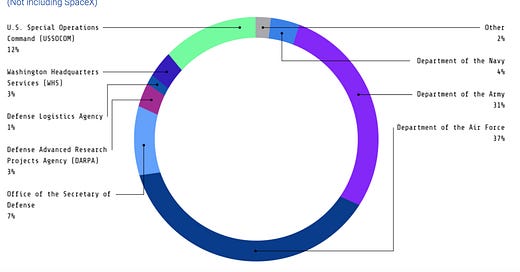

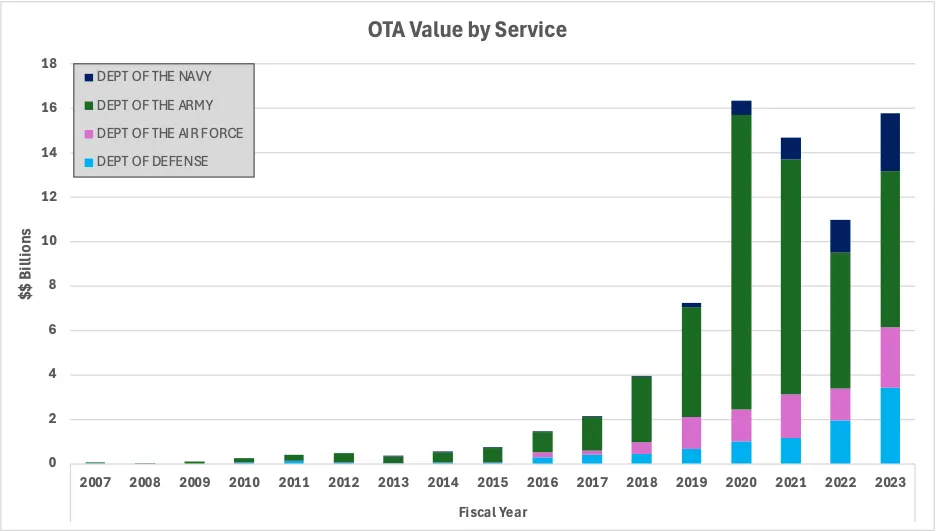

The Navy invests significantly less in technology developed by innovative, VC-backed startups than other services. Of the total contract revenue received by the SVDG NATSEC100 startups, only 4% of that revenue came from the Navy (compared to 31% from the Army and 37% from the Air Force). Another relevant metric is services’ spend via Other Transaction (OTA) contracts, more flexible DoD contracts that are often used by startups to shorten the acquisition cycle: the Navy has spent only $7B on Other Transaction Authorities (OTAs), compared to the Air Force’s $15.9B and Army’s $53.2B. Finally, the Navy has only about $1B set aside for RDT&E related to AI, compared to the Air Force’s $2.6B and the Army’s $2.9B.

While the Navy as a whole tends to be less innovative than the other services, there are pockets of innovation where forward-leaning technologists are navigating the system to drive meaningful improvements. For example, PEO Digital has developed an Innovation Adoption Kit for any PEO to speed up procurement and work with an expanding vendor ecosystem. The kit defines outcome-based metrics to guide prioritization and structured piloting for speed, enabling PEO Digital to significantly shorten software procurement timelines. While procurement can take more than five years in other parts of the DoD, PEO Digital’s process allows them to procure software, including AI software, within just a few months.

Early Adopters

One metric we calculated to evaluate the Navy’s willingness to adopt new technology: how many vendors get their first AI / ML or autonomous systems related contract with the Navy vs from another service? How about their first five? While this metric is not perfect, it gives us a glimpse into how quickly the Navy is willing to adopt new technologies.

Although the Navy actually spends more than the other services on AI and autonomous systems (note that the majority of the value of these contracts goes to legacy programs like Aegis missile defense system and the F-35, which use some limited AI and autonomy technology), the Navy rarely awards vendors their first (or first five) contracts for these new technologies. Startups are heavily reliant on finding early adopters for their technology in order to provide crucial early feedback during the product development process. Today, the Navy is not the ideal partner for startups given its slow adoption of buying new technologies.

The Navy awarded 25% of vendors’ first contracts related to autonomous systems, compared to 35% from the Air Force and 40% from the Army. The Navy lags further behind the other two services with regards to awarding vendors their first contracts related to AI, awarding just 16% of vendors’ first AI contracts, compared to 24% from the Army and 60% from the Air Force.

Force Structure

In case you haven’t heard, the Navy loves ships. With WW3 looming, they love stealthy submarines (which are boats, not ships) even more. They also have the second biggest air force in the world, after the US Air Force. The problem with complex, expensive platforms: they’re tough for startups to build. Startups excel at biting off very specific “beachhead problems,” building cheap “minimum viable products” to demonstrate a concept, gaining customer traction with focus and speed, and then scaling to solve bigger problems. Building a large complex system of systems over many years without customer feedback is much safer for a large company on a guaranteed cost plus contract. Let’s look at how much of the Navy’s budget gets spent on these big platforms.

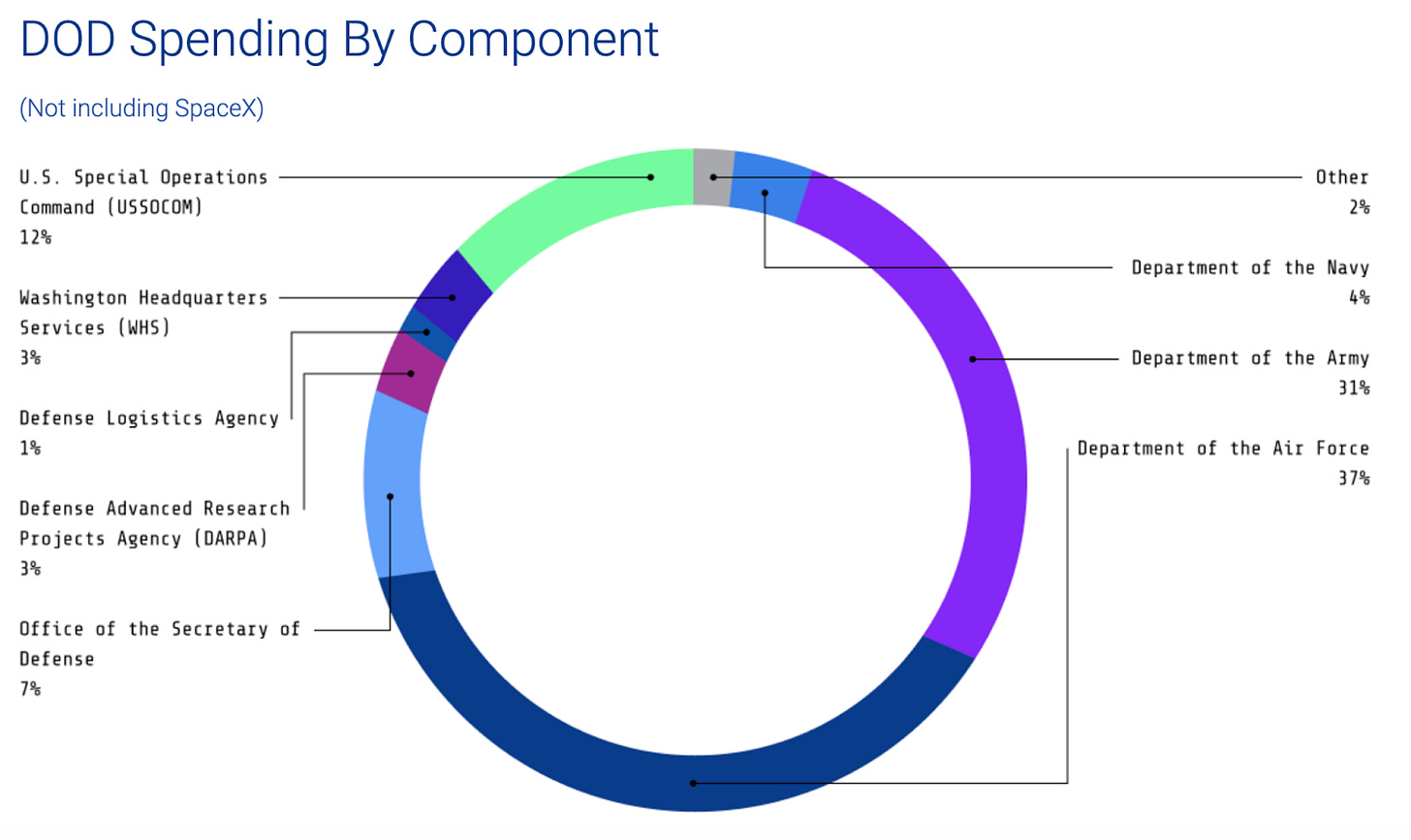

First, it’s key to remember that the Navy has roughly the same size budget as the Air Force, and a fair bit more than the Army. The Navy would still be $204B without the Marine Corps, which as a ground force (“the Navy’s Army”) buys equipment more similar to the Army equipment than Navy or Air Force equipment.

From the Navy’s budget, almost half goes toward major weapons programs like shipbuilding and aviation. With $48B spent on shipbuilding, $20B spent on aviation, and another $10B on munitions. Munitions are also tough for startups to make. That’s $80B of the budget on the Navy’s core tech that startups are highly unlikely to compete for. While we’ve met one munitions startup and two shipbuilding startups, there aren’t many competing in the space, for good reasons.

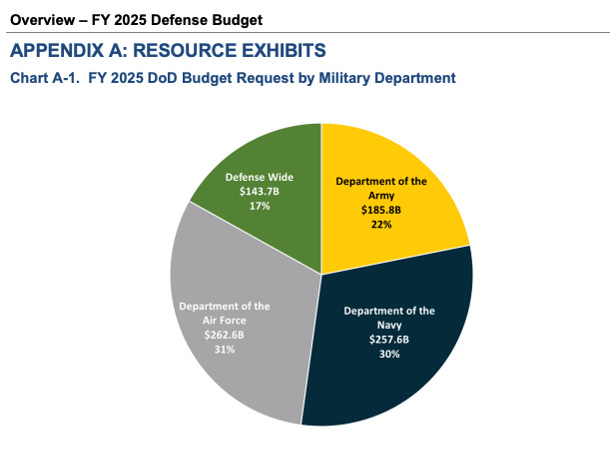

The capabilities startups are likely to compete for are commercial tech like software, communications, computing, and sensing: that basically boils down to C4I systems. The Navy has the smallest spend on C4I of any service.

Ground systems are also easier for startups to tackle, thanks to their overlap with commercial markets like automotive and their relative simplicity compared to aircraft and ships. Ground systems can often be fielded by a single soldier, making them easier to adopt quickly. That’s a far cry from the time and complexity required to integrate new tech into a warship or aircraft.

In addition to C4I and ground systems, RDT&E S&T is also considered a more startup friendly color of money, since it is tech-focused. But most RDT&E is tied to future programs of record, because tech that doesn’t transition is considered a waste. Therefore, much of the Navy’s RDT&E dollars end up focusing on developing and testing the same ships and aircraft startups struggle to contribute to. For example, the Navy may have a nice R&D budget, but $5.5B of it goes to developing tech for ships - making it tough for startups to compete for.

Needing lots of ships and planes means the Navy has to rely more on MDAPs (Major Defense Acquisitions Programs), decades-long, complex processes run from the Pentagon that startups generally cannot compete for. The GAO numbers above show that the Navy has most of DoD’s MDAPs. The Navy’s bureaucratic culture is also highlighted by the small number of Navy MTA (Middle Tier of Acquisition) programs, which emphasize rapid prototyping and faster fielding.

The complexity of integrating a product that can compete for a major program is captured effectively in the below GAO chart. The chart shows each platform depending on multiple core enabling technologies. There are many dependencies, multiple failure points, and despite being on the “MTA fast track”, all of these programs have been running for years without completion. Of note Anduril recently took the helm on the IVAS program, listed on the bottom, after Microsoft struggled to field it. We’ll be watching.

If we step back to the initial frame with the services having roughly similar size budgets, the Navy is spending easily the most as a share of its budget on large, complex platforms. These ships and aircraft take large amounts of capital, time, and process to build and compete for. On top of having the most complex products, the Navy is routinely choosing the most complex acquisition pathways to manage them. If there’s one thing startups cannot afford to burn, it’s time.

Startup-Friendly Contracts

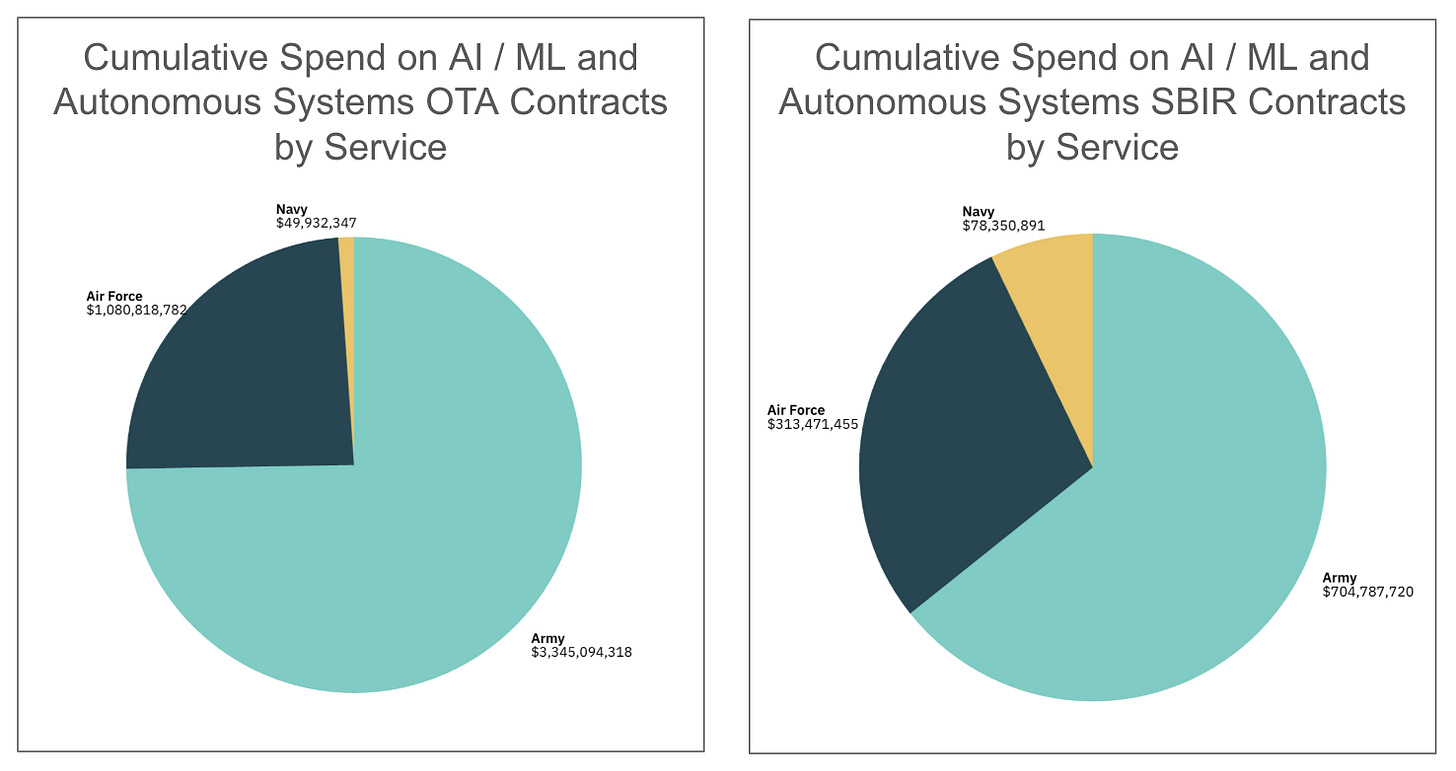

Another metric we analyzed to assess Navy’s startup friendliness is the Navy’s use of startup friendly contracts such as Other Transaction Authorities (OTAs), Small Business Innovation Research grants (SBIRs), and firm fixed price contracts. Once again, the Navy significantly lags behind the other services in employing these more startup friendly contracting methods when procuring AI / ML and autonomous systems. The Navy spends significantly less on OTA and SBIR contracts than the other services. OTA and SBIR contracts benefit startups because they offer flexible, streamlined pathways to work with the DoD. These vehicles enable faster funding, quicker prototyping, and lower barriers to entry, allowing startups to demonstrate value and gain traction inside the defense ecosystem.

Even when not specifically procuring AI / ML and autonomous systems, the Navy uses OTAs less than the other services. The Navy has spent only $7B on Other Transaction Authorities (OTAs), compared to the Air Force’s $15.9B and Army’s $53.2B. For reference, startups that have successfully used OTAs to field AI and autonomous systems to DoD include Skydio, Arize AI, Shield AI, Primer AI, Maxar, and Weights and Biases, among others.

The Air Force in particular is a real leader in working with small businesses and startups to develop and acquire AI-enabled products. The Air Force has significantly more SBIRs related to AI/ML than other services, and Air Force AI/ML SBIRs appear to have consistently higher transition rates compared to the other services (again, huge thank you to Lt. Col. Chris Berardi for letting us use some of his previous analysis here).

Further, the Navy tends to have less competitive contracting processes for AI / ML and autonomous systems compared to the other services. Only 12% of the Navy’s AI and autonomous systems related contracts were available for competition, compared to 26% for the Army and 30% for the Air Force.

One place where the Navy does not lag behind the other services is in its use of fixed price contracts. The Navy uses fixed price contracts at a similar rate as other services. 31% of the Navy’s AI and autonomous systems contracts are fixed price, compared to 32% for the Air Force, and 44% for the Army. However, if you look at the percent of contract dollars that go to firm fixed price vs. cost plus contracts, the Navy spends 78% of total AI and autonomous systems dollars on firm fixed price contracts (compared to the Army’s 76% and Air Force’s 19%) thanks to a few large firm fixed price incentive contracts with Lockheed Martin. Fixed price contracts are generally better for startups than cost plus contracts because they offer predictable revenue, fewer compliance burdens, and align with the way startups operate: lean, fast, and focused on delivering outcomes. With fixed price, startups can move quickly, keep any savings from efficient execution, and avoid complex accounting systems and oversight required under cost plus agreements. This model supports scaling, aligns with commercial practices, and lets companies focus on building and delivering, not navigating bureaucracy.

Navy Program Offices

Last fall at a Navy industry day, I (Austin) struck up a conversation with a man outside the bathroom during a break. He turned out to be a program office lawyer. When I asked about his goals for the event, he said he couldn't share them with me, a "contractor." Puzzled, I asked why he was even there. If he couldn’t talk to industry at an event designed for industry-government information exchange, why had he flown across the country?

His answer was unsettling: his role was to monitor the government team and make sure they didn’t say anything unapproved to industry. At a forum meant for open exchange, he was there to enforce silence, sitting quietly in the back, watching. Big brother.

Navy program offices are not alone in suffering from cultural risk aversion. Layers of lawyers, regulation, and reporting hamstring great Americans who hope to buy the best tech for warfighters. But the culture in some Navy program offices is notoriously bad. What I saw at that industry day - the most awkward 30 second professional conversation of my life - demonstrates how some offices are hamstrung by lawyers and risk aversion. Let me say explicitly in case it is unclear: I have deep respect for program office and acquisition professionals. They have important, challenging jobs and are under tremendous pressure to deliver capability. The system is complex. It needs reform.

But this evidence is only anecdotal. Let’s get to the numbers.

Navy’s program offices, probably against the advice of their lawyers, deserve credit for publishing excellent demand forecasts, known colloquially as Long Range Acquisition Estimates (LRAE). The Army publishes similar reports, but they are not as detailed and transparent.

Looking at the LRAEs for the Navy’s major acquisitions offices suggests just how hard it is for new companies to work with and sell to these commands. In the chart below, Naval Sea Systems Command, which buys ships, submarines, and other maritime systems for the Navy, projected 793 contracts for fiscal year 2025 only:

128 (16%) could be performed by a contractor without a security clearance.

33% were new contracts or recurring contracts that lacked an incumbent.

44% would follow a fixed price structure, and

1% would use an Other Transaction contract vehicle.

29% of them, often not the same as the newly competed ones, were already set up as sole source awards, leaving only 71% open for any type of competition.

Any one of these conditions could disqualify a startup from competing for a contract. Most contracts require facilities clearance, and almost all have an incumbent or a sole source designation. Only 61 of NAVSEA’s 793 contracts, or 8% were planned to be new contracts, not sole sourced, and not needing facility clearance.

For Naval Air Systems Command, which develops and buys air platforms for the Navy, many of the statistics are similar, although a smaller share of contracts require security clearance. Incredibly, 1045 of NAVAIR’s 1467 contracts (71%) are planned to be sole source in 2025, leaving just 29% open to any type of competition, less after accounting for incumbents, set asides, and other competition-killing conditions.

The Office of Naval Research (ONR) appears more competitive, except that it plans to issue so few new contracts. Of the 5 new contracts for 2025, most are sole sourced or have an incumbent.

The Marine Corps Forces Systems Command (MARFORSYSCOM), which procures much of the Marines tech, and Naval Information Warfare Systems Command (NAVWAR) which develops and procures most of the Navy’s C4I and information systems, both appear to enjoy more open and competitive contracting processes than the big platform Navy research and procurement commands. Both use OTAs and simple fixed price contracts more frequently, and have more new and fewer sole sourced contracts than their peer Navy commands. Unlike the Navy procurement commands, the majority of Marine Corps programs don’t seem to require a facilities clearance, a huge barrier to entry for any small company.

Sadly, such data is not available for the other services. While the Navy deserves credit for publishing such through acquisitions forecasts, the data suggests Navy really is quite hard to sell to, even if a company can build the big platforms the fleet is built around. The root cause of this challenge is hard to pinpoint - one hypothesis from GAO is that the acquisition workforce is struggling to hire key technical acquisitions talent.

What can be done to get more startups and new entrants solving Navy tech problems?

We’ll analyze this from the perspective of four key stakeholders:

Startups

Incumbents (e.g. Primes)

Investors

Government

What should startups do?

First and foremost, startups intending to sell to the Navy must ensure they are building a product that solves a real Navy end-user pain point with real budget attached (for more on DoD budgeting trends related to AI and autonomous systems, see this blog post)! We also highly recommend checking out Vannevar’s two part series on how tech startups should approach building for and selling to the DoD. Selling into DoD will always be challenging. It is crucial that startups have champions within the Navy willing to fight through bureaucracy in order to field their product.

Startups must play to their strengths when selling into DoD. What can startups do better than the traditional defense primes? Startups are good at quickly developing cost-effective minimum viable products by leveraging affordable commercial technology, collaborating closely with customers to understand their needs, and rapidly iterating to best fit customer needs.

What aren’t startups good at? Startups are generally not good at building highly exquisite, expensive hardware platforms that require significant investment in R&D like aircraft carriers and fighter jets. Startups looking to sell into the Navy (and the DoD as a whole) should not try to build these kinds of expensive, exquisite hardware platforms, as this is what the defense primes are set up to do. Instead, startups should focus on developing powerful software solutions that enhance existing legacy hardware platforms or rapidly and cost-effectively build hardware systems using commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components integrated with advanced software.

Startups should also explore opportunities to collaborate with more traditional defense primes as a subcontractor or partner on defense prime contracts, where they can deliver significant value by building, deploying, and rapidly iterating software applications and COTS hardware solutions that enhance prime-built hardware platforms. For example, aerial autonomy software startups Shield AI and EpiSci (acquired by Applied Intuition Defense) have worked with more traditional defense companies like General Dynamics and Kratos to build autonomy software capable of piloting their more exquisite hardware platforms like the F-16 and MQM-178 Firejet. Similarly, autonomous surface vessel (ASV) startup Seasats has partnered with L3Harris to outfit Seasats’ ASVs with L3Harris networking payloads.

To accelerate the speed to deploy systems, startups should also become intimately familiar with DoD processes and standards like the DoD’s cybersecurity requirements, the ATO process, supply chain requirements, and MIL-SPEC and MIL-STD performance requirements. It will also be critical for startups to understand the computing hardware limitations for the systems they plan to deploy onto; many DoD hardware systems are not equipped to run compute-intensive software. For instance, a Tesla Model S car has 10 times the computing power of an F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Startups may also consider making some part of their product available open source. If a product is open source, DoD personnel can easily experiment with the product without any of the arduous compliance processes (like the ATO process) typically required to deploy software on DoD systems. After the DoD has started using a startup’s free, open source product, the sales process for the paid product will be much quicker, as DoD end users are already familiar with the product and can serve as champions throughout the acquisitions process.

Where possible, startups should also look to work with more forward leaning groups within the Navy like PEO Digital and Task Force Hopper, an initiative to streamline information sources and operationalize artificial intelligence capabilities across the Navy’s surface fleet. Leaders in these groups are actively focused on accelerating the acquisition of emerging technologies. They can help companies navigate complicated government compliance and testing processes, provide product feedback, and serve as connectors into Big Navy. However, these teams don’t have the traditional source of power in the bureaucracy: budgets and personnel. PEOs with both need to learn from them.

What should the defense primes do?

Defense primes need to recognize that startups can drive real value as subcontractors. For example, defense primes often lack top-tier software engineering talent and should prioritize enabling software-focused startups to seamlessly build on their hardware platforms whenever possible.

The difference between an incumbent who adapts and one who stagnates could be their ability to work with others. On the most complex tech, even a big incumbent company needs partners. And in some cases, lean startups make the best partners.

What should the Navy do?

Many gold-plated reports and proposals already explain what DoD should do to buy better tech and shape a more competitive market for defense capability. You can read them here, here, and here. This discussion is focused solely on what the Department of the Navy, uniquely, must do.

Above, we identified that the Navy buys uniquely large and complex systems. To increase competition in the market for these systems, we have three recommendations for the Navy:

Buy and integrate more commercial tech

Supercharge prototyping of naval platforms

Set up COCO training wheels to get new tech through the first few years of DOTMLPF challenges, moving toward GOGO as quickly as the force can adapt

First, get more commercial tech onto these platforms. When I (Austin) last sailed on an aircraft carrier, our internet browser was years behind that on land. Second, and more importantly, the Navy needs a supercharged innovation office, like DIU, with a hefty and ambitious prototyping program. Because the Navy will always need ships, boats, and aircraft, the Navy should create mechanisms to let companies compete and innovate to build these platforms. Supercharging the Disruptive Capabilities Office with a budget and contracting authority and charging it to prototype 10 naval platforms per year ranging from $2 - 25 million would help bring new tech into the fleet. If such an office had existed, venture capitalists would not have had to finance most of the USVs and UUVs you can name.

A naval officer’s argument against the above supercharged naval prototyping office: the tech won’t transition. The Navy presents a uniquely challenging transition environment, where integrating new technology must align with sophisticated concepts of operations like ship-to-ship refueling, long supply chains, and limited communications bandwidth, making it difficult to find the right fit.

With all the unmanned tech the Navy has tried in recent years, the challenge is not finding good tech, but adopting and integrating it into the fleet. Navy bureaucrats gripe about the DOTMLPF challenge of new tech, because once they find the tech, they have to figure out how to maintain, repair, house, and refuel the equipment. They also have to recruit sailors, train them, lead them, and create units to organize them. Any new tech transitioning into the military needs DOTMLPF, and the Navy’s is especially challenging.

So what the Navy needs is a set of DOTMLPF training wheels. Once it finds a cool prototype, the Navy should let contractors operate the technology in a contractor-owned contractor-operated “COCO” model during the first year of operations, while government writes manuals and looks for sailors to operate the tech. Once some sailors are found, they could start operating the tech, with training from the contractors, and eventually start maintaining it themselves. In short, contractors can start doing all of the DOTMLPF functions, and hand them off over time to sailors. Some of the functions, like advanced training and maintenance, might be best left with contractors.

Last, the Navy has deep cultural problems when it comes to buying tech. These can only be addressed by pure, tenacious leadership.

What should private capital allocators (VC + PE) do?

As I’ve (Maggie) written about before, investing in DoD-focused startups is very different from investing in traditional SaaS companies. It is important for venture capitalist (VCs) and private equity (PE) firms investing in the space to understand the eccentric nature of selling to DoD. Startups focused on selling to DoD are unlikely to have a smooth “hockey stick” growth trajectory like SaaS startups. DoD contracts tend to be large and lumpy; a startup may have no meaningful DoD revenue for its first five years, and then finally get on a program of record worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Laying the groundwork to shape requirements and secure significant budget for a startup’s product takes years. The DoD’s budgeting process begins three years in advance, meaning a startup must take action now to secure funding for 2028. VCs should not pressure their portfolio companies to seek an exit or liquidity prematurely, just because DoD contracting takes longer than they realize. VC firms with portfolio companies selling into the Navy in particular need to understand that the Navy is a slow buyer.

VCs should look to invest in startups building new capabilities that can fit under existing Navy requirements that solve real end user pain points with strong internal champions. There can be many ways to solve a particular problem, and VCs should look to fund companies that solve existing, identified Navy problems (with enough real procurement budget to justify venture returns) in a new and better way. For example, consider a surface warship’s missile defense system: there are two approaches to defend a surface warship against an enemy missile attack – “hard kill” (kinetic interceptors like missiles) and “soft kill” (electronic warfare to jam or mislead incoming threats). Soft kill systems, often software-defined, are cheaper and more repeatable, while hard kill systems are costly and can quickly run out of ammo. Both aim to stop incoming missiles, but each comes with trade-offs in cost, reliability, and scalability.

Private equity (PE) firms that buy majority stakes in defense-focused businesses also have a role to play in the DoD-focused startup ecosystem. Many PE firms see aerospace and defense as an attractive sector to invest in given the industry’s high barrier to entry. Many DoD-focused companies have spent years building deep tech and customer moats, investing heavily in R&D and relationship building. Additionally, military spending across the world is expected to steadily increase over the next decade. PE firms can provide liquidity to startup founders and early investors, while also helping DoD-focused startups scale by injecting capital to streamline operations and compete for large contracts.

Firms pursuing a “roll up” strategy can further boost efficiency by centralizing functions like lobbying, defense contracting, and business development, freeing up portfolio companies to concentrate on R&D, manufacturing, and deployment. As Austin previously wrote, “Building and selling defense product has insane amounts of overhead. Facilities clearance, compliant supply chains, and special accounting methodologies – these are all back office functions that only a large company can efficiently absorb. Larger companies can spread the cost of expensive, specialized support teams like IT across several business units.” PE firms can help companies manage that overhead.

Conclusion

While the U.S. Navy faces pervasive structural challenges that will always make it a tough customer for startups, complex platforms, risk-averse culture, and slow and complex contracting practices, we see clear opportunities for progress.

Startups can succeed by building software-first solutions tailored to end-user needs; primes can benefit from partnering with nimble innovators; and investors must be patient and strategic in backing companies that align with real Navy requirements.

Most importantly, the Navy must evolve. Embrace more flexible contracts. Empower innovation offices. Create smoother on-ramps for transitioning new technologies into the fleet. We do not have time to waste.

The Navy will lead any future conflict in the Indo-Pacific, and must be ready to project power across vast distances, integrate autonomous and software-defined systems at scale, and outpace adversaries through rapid innovation and operational flexibility. Success will depend not just on the technologies we develop and how much capital startups can raise, but on how quickly and effectively we can bring that technology to the fight.

Important information; productive suggestions and insights; great read!

Get this thing on foreign affairs. Great piece.