Defense M&A and the Deal Flow Dinner

New primes are being built

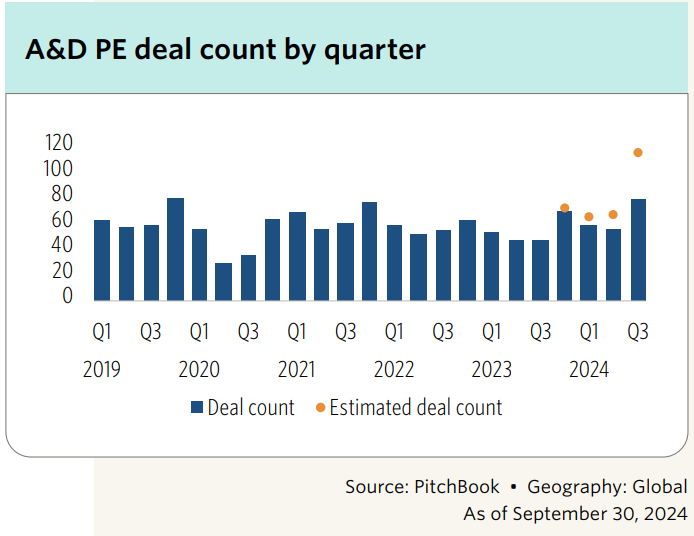

Deal-flow in defense might be ready for its moment. Last week, Applied Intuition announced its acquisition of EpiSci, diversifying the ground-heavy autonomy leader into more domains. Last month saw a billion dollar Edge-Redwire deal (more below), and last year saw many significant mergers and acquisitions in defense, aerospace, and shipbuilding.

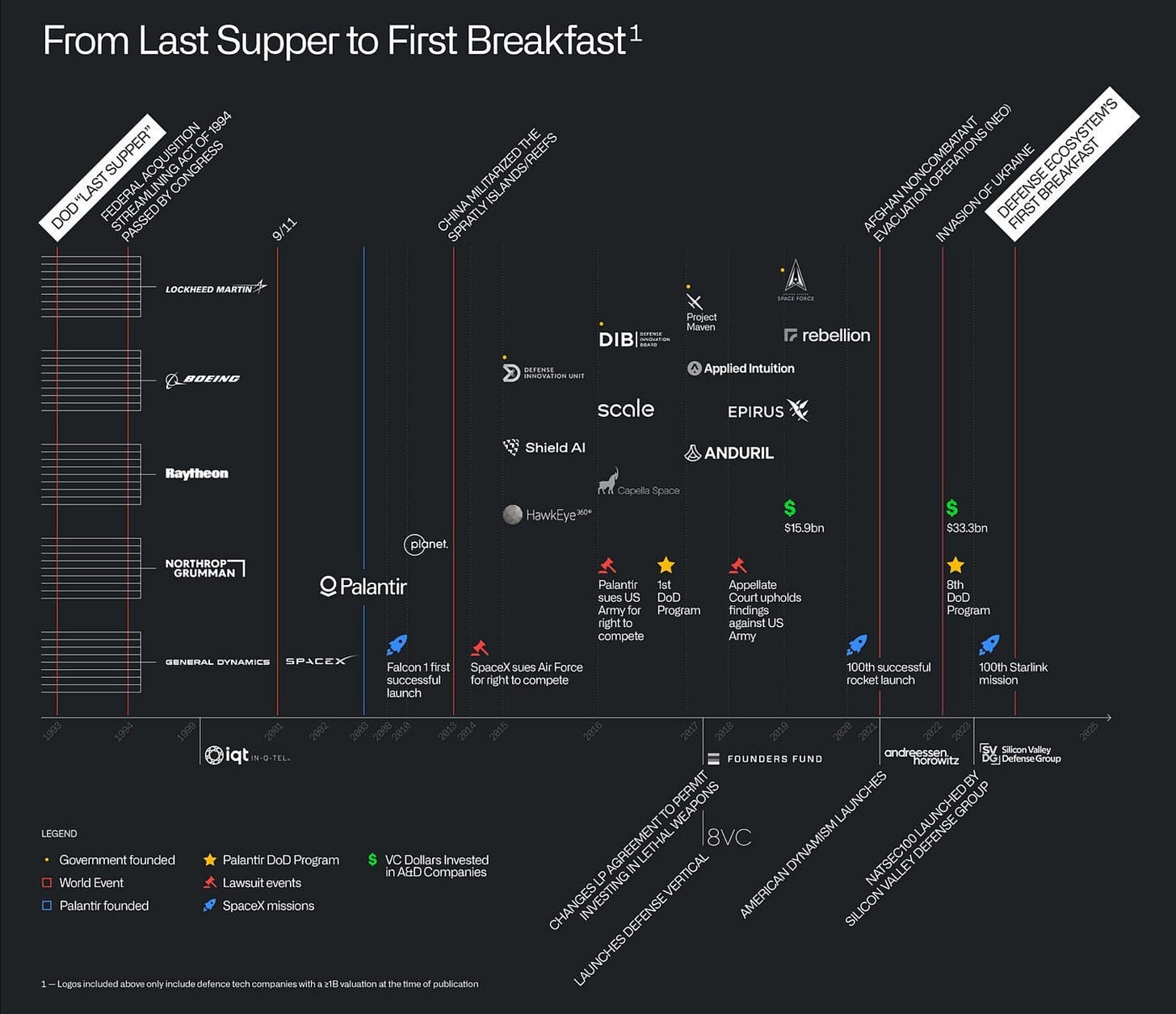

In this piece, I will argue that defense M&A is the key to unlocking a vibrantly competitive defense industrial base over the next five years. The First Breakfast theory – named because it corrects for the consolidation following the Last Supper, and welcomes new entrants who can restore competition to the defense industrial base – is inspirational.

But in addition to a First Breakfast, we need a Deal Flow Dinner.

My analysis suggests that most VC-backed entrants, those breaking bread at the First Breakfast table, are not yet ready for M&A prime time. Although Palantir, Anduril, and SpaceX have sat, most are still cueing in the metaphorical Tatte line, wondering whether to order a healthy blueberry bowl or a greasy skillet. Most are still startups, and are grateful they have graduated to Tatte, after years running off Dunkin. They’re not ready to buy other companies and take on big primes.

Growth-stage firms, many of which are private-equity-backed or already publicly traded, are ready. On the M&A markets, they will continue to grow. They can build corporate capability with diversified tech stacks. They can compete head-to-head with the incumbent primes across many verticals. And they can acquire other companies to build the future. The Deal Flow Dinner is how they do so.

Before getting into the piece, I want to thank the real finance professionals who contributed to it. Several investors and analysts, some of whom may have worked on deals discussed below, shaped the thinking you’ll see. Mistakes are mine.

Rough Outline

Recent M&A Examples

AVAV x Blue Halo

Redwire x Edge Autonomy

Huntington Ingalls x W

Key takeaways: a more competitive defense market

Diversification

Supply Chain

Liquidity

New Entrants, New Primes & M&A Power Players

What the VC-backed entrants are up to

Time for the Deal Flow Dinner

Recent Defense Mergers & Acquisitions

Analysis of the market and a few key deals from the past year shows that corporate development in defense, aerospace, and shipbuilding has one core purpose: building more competitive companies. On the healthier side of this purpose, growth-stage companies are diversifying into new domains, and building multi-billion dollar beasts that can compete with the behemoth incumbent primes. On the other side, we find incumbents shoring up anemic supply chains. Both are preparing for an increasingly competitive era.

First, let’s set the stage with three of the 2024’s biggest deals. If you’d like more information on these companies, please click the link on the word “merger” or “acquisition.”

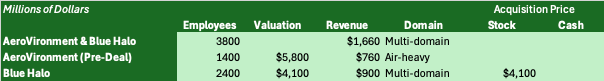

AeroVironment (AVAV) x Blue Halo Merger

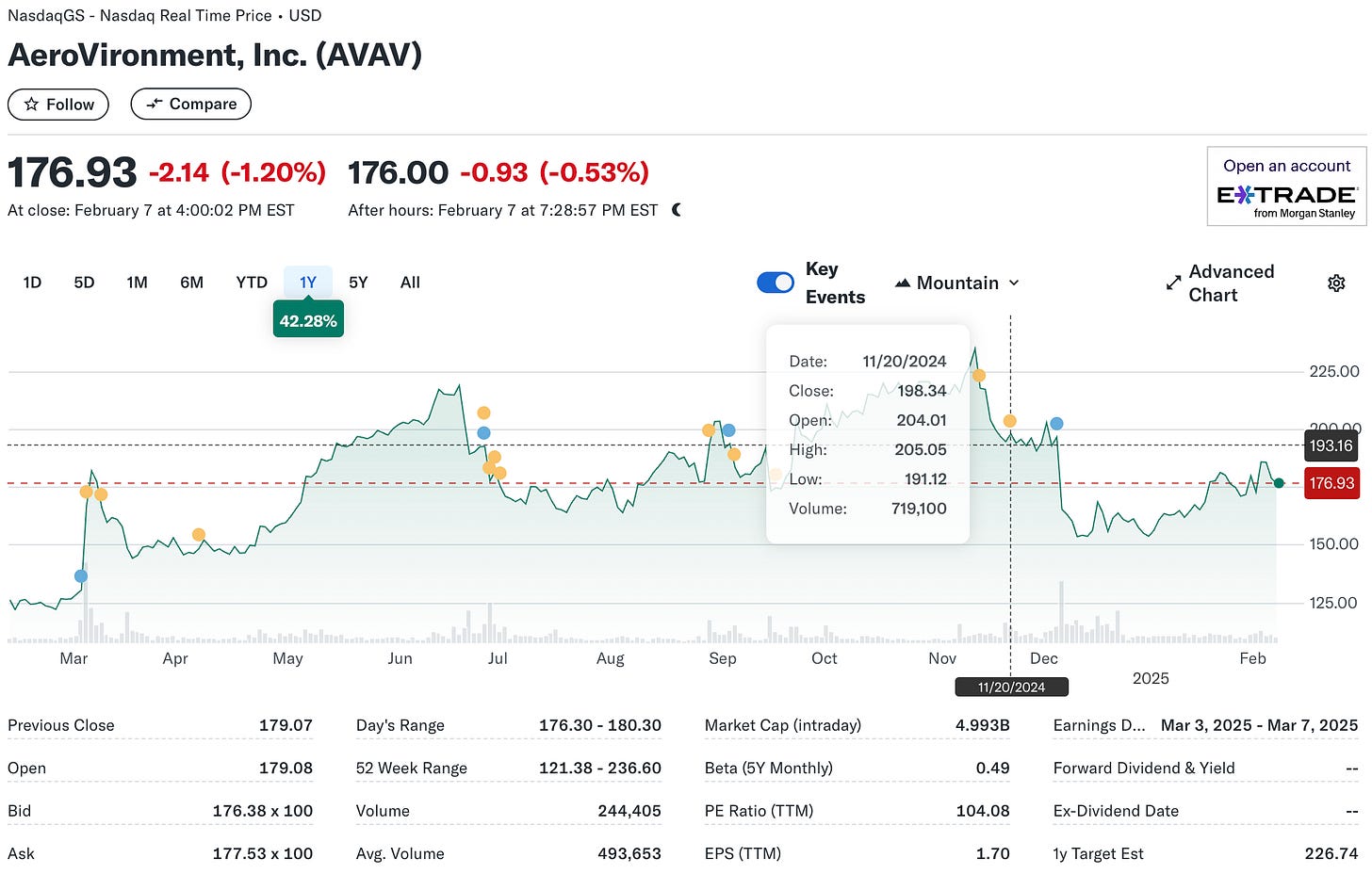

Soft earnings in AeroVironment’s core business, such as loitering munitions, are a big part of why they needed to merge with Blue Halo. Not only have recent earnings numbers missed targets, but much of AeroVironment’s revenue comes from Ukraine. The Ukraine-Russia war provides a bad ass proving ground for AeroVironment’s drones, but such revenue is not locked in for decades like US DoD programs of record, so defense companies don’t get much credit for it with wall street analysts. Acquiring Blue Halo allows AeroVironment to diversify its tech and revenue, despite recent success with drones in Ukraine.

On the other side of the table, Blue Halo and its private equity backers Arlington Capital Partners – they get the exit their investors expect, and one tough to come by during a limp IPO market. Although this was a stock-stock deal, not a cash acquisition, AeroVironment’s stock is publicly traded, so the merged firm is public and Blue Halo’s investors trade their illiquid private stock for more liquid public stock; they’ll be able to cash out soon.

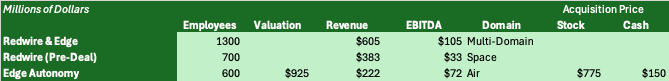

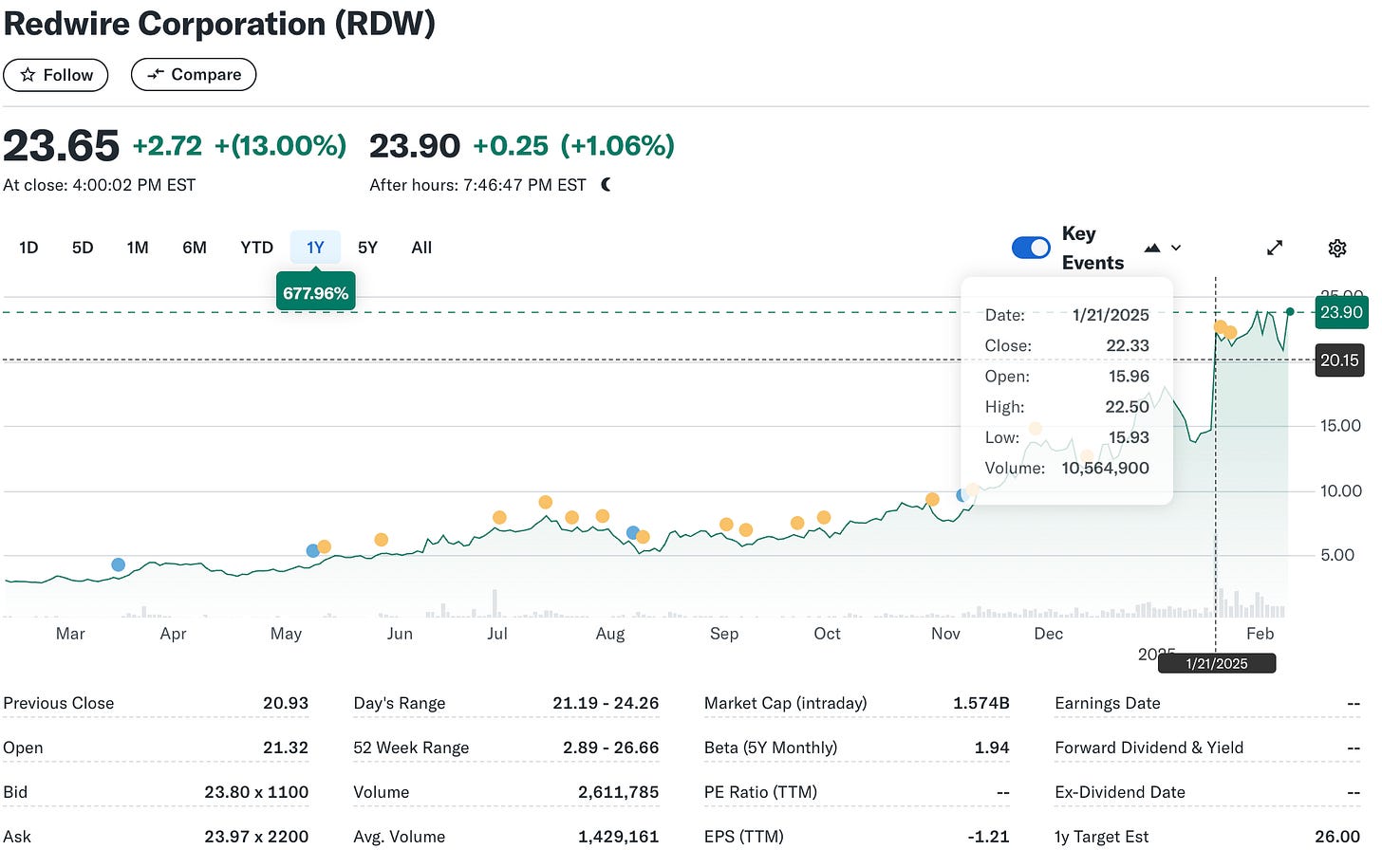

Edge Autonomy acquisition by Redwire (RDW)

Diversification is also a key takeaway from this deal. Redwire’s space capabilities have a vibrant commercial business and a growing defense presence. In defense, Redwire has been moving into lower-earth orbits where it seeks to bridge the gap between satellite- and aircraft-based sensor data.

To complement its satellite constellation, Redwire found Edge, which makes higher-end uncrewed air systems. This acquisition makes the combined Redwire a multi-domain company with strong air and space technology and revenue streams. Like the AVAV x BH deal, this one also gives Edge Autonomy and its private equity share holders at AE Industrials more publicly-traded Redwire stock.

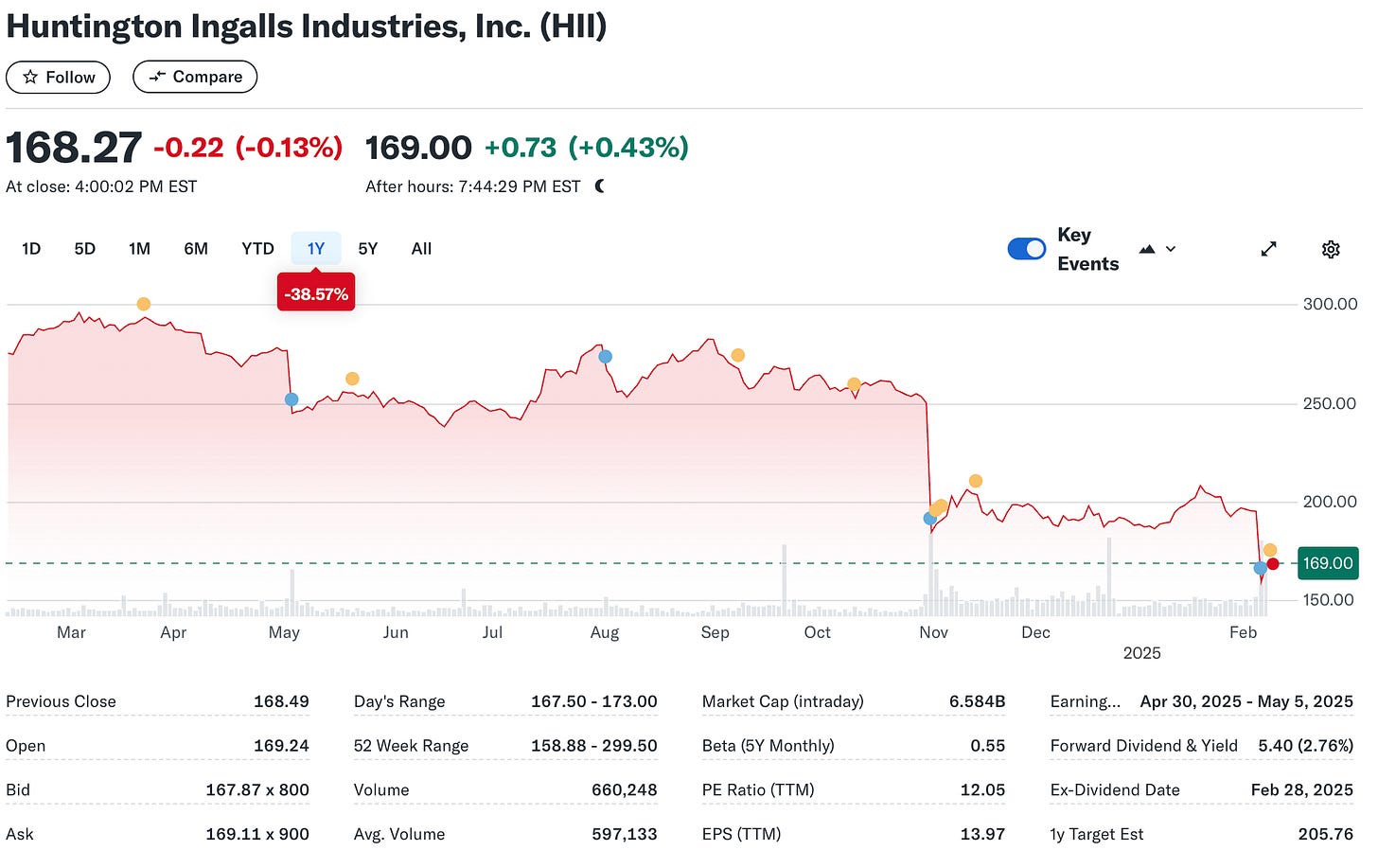

W International acquisition by Huntington Ingalls Industries (HII)

Not all deals point to diversification though. Huntington Ingalls, the biggest defense shipbuilder, acquired W International, which was previously an HII supplier. Shipbuilders like HII have long sought to outsource their supply chain, a strategy that protects margins. But additional demand and a weak supply chain means prime shipbuilders like HII could all be bidding work to the same suppliers, in order to satisfy Navy demand. In cases where demand is weak, primes and integrators can’t risk their critical suppliers collapsing.

Several of the big shipyards enjoy a monopoly on assembling very specialized ships like nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers. Supply chain acquisitions like W re-enforce their position further down the value chain. This acquisition suggests HII was feeling the pain in supply chain. And these takeaways are re-enforced by similar M&A in the shipbuilding supply chain, such as of KEEL, Philly Shipyard, and Alabama Shipyard.

Key Takeaways: A More Competitive Defense Market

The deals above exemplify healthy pressure on companies to compete. This is good for DoD customers and is driven by three key incentives.

Grow Multi-Domain Capability: Companies with growing success in single domains are noticing an opportunity to compete across multiple. For example, CACI acquired Azure Summit for $1.3B – bringing “complementary” technology into a growing portfolio. This M&A trend matches the trend in warfare technology: multi-domain, networked operations drive lethality on the battlefield. Additionally, building and selling defense product has insane amounts of overhead. Facilities clearance, compliant supply chains, and special accounting methodologies – these are all back office functions that only a large company can efficiently absorb. Larger companies can spread the cost of expensive, specialized support teams like IT across several business units.

Strengthen Supplier Base: Where M&A does not grow multi-domain competitors, it prepares incumbents to protect their core business. Ship and Submarine components, where supply chains are especially vulnerable, highlight this trend. In aerospace, Boeing acquired Spirit, a mission-critical supplier at risk of collapse, as commercial business suffered.

Find Liquidity: Investors always want exits, and IPOs are not the only way to achieve liquidity. Stock-stock deals appear appealing, and a stock-heavy acquisition by a publicly traded company is a nice way to backdoor an IPO. Because many large defense companies rely on low-margin, cost-plus contracts, they don’t have large amounts of cash, and will likely continue to pursue stock-heavy deals.

The Pentagon and the big legacy primes are facing a moment where competition is driving change. Be it from geo-political winds, domestic ones, or more predictable market and technological forces, the market for defense products is accelerating, and with more players.

New Entrants, New Primes & M&A Power Players

The VC-Backed Entrants

Zero of the companies mentioned so far are venture-capital backed. The acquirers are publicly traded industry leaders, either diversifying in their growth stage or protecting their moat as incumbents. And the acquisition targets all have serious revenue and earnings. Basically, their financials are better than most VC-backed companies.

Anduril, among other VC-backed new entrants, has made corporate development a cornerstone of its growth. Thanks to one of those acquisitions, Anduril is competing directly for the Collaborative Combat Aircraft program of record and, with the other finalist General Atomics, has displaced traditional incumbents from this program – a total coup. If you squint and look closely, another acquisition in the undersea space may allow Anduril to knock Boeing off the troubled XLUUV program. Among the VC-backed entrants, Anduril, Palantir, and SpaceX alone have the revenue to buy other companies without great dilution from additional debt or equity.

Most VC-backed firms simply do not have the balance sheet to support or be the target of M&A. Only a handful of firms have revenue over $50M per year, which is much lower than that of the acquisition targets we’ve analyzed above. Among those, sky high valuations disincentivize founders and boards to sell, because they would have to accept a down round closer to the value tied to revenue to do so. Many founders would get nothing from an exit at a valuation tied to their current revenue. Although they aren’t good acquisition targets, many of these firms could become strong acquirers at later stages, as Anduril has.

The New Power Players

The power players in this environment are those with strong domain focus, and a numbers-backed story about how they could soon dominate that vertical. When they are the acquirer, these players already know what they are good at. Self knowledge makes it easier to justify an acquisition in a new space. Redwire, for example, saw a crystal clear opportunity to find synergies between space and air capabilities. On the other side of the deal table, it might make a company a better acquisition target if it has strong focus, either in a warfare segment (like Blue Force and Dive) or in the supply chain.

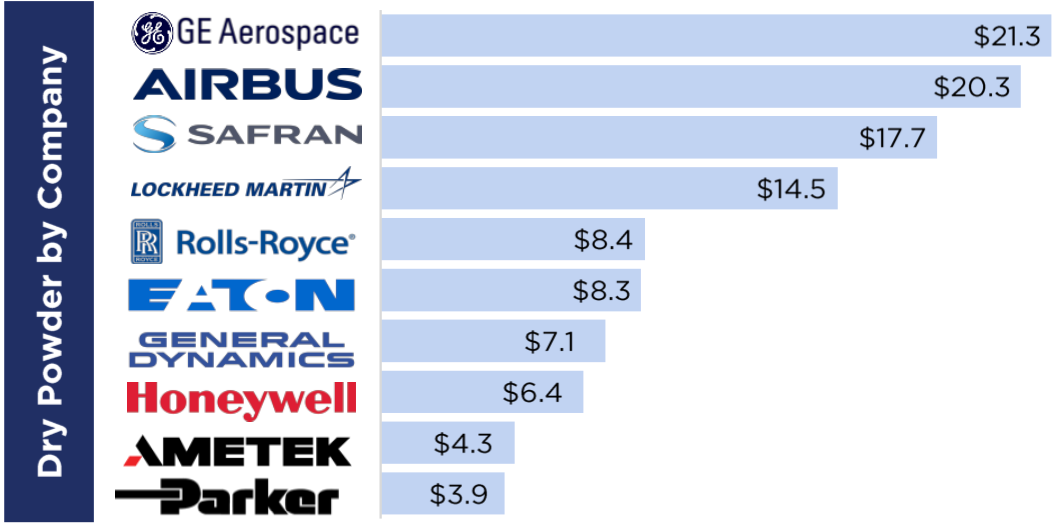

This diversification logic may explain why we have seen few recent acquisitions from the biggest primes: they are already diversified. Since Lockheed and Raytheon already have capability across many technology and customer verticals, it’s harder for them to identify clear gaps in their capability matrix that should be filled with acquisition. Simply put, they have a tougher matching problem. Additionally, as large organizations, it takes longer to build consensus to execute on a deal. However, companies like Lockheed and GE Aerospace have the most cash on hand to make acquisitions.

One storied M&A myth is that the market dries up significantly for deals over $500M. The deals above purposefully bely that stereotype. However, it has some merit. In the same way that Lockheed with a big portfolio might struggle to solve key matching problem math that justifies an acquisition of even a very focused company, the target company having a big portfolio also complicates alignment. A bigger acquisition target, such as a $1-2B company, might have two or three key verticals, greatly raising the probability that part of the business complicates a potential acquirer’s goals. Fitting a single jig-saw piece into the puzzle you’re assembling is simple once you find the right piece – fitting several together simultaneously can be awkward.

If alignment isn’t challenging enough, acquisitions over $1B are tough for the simplest reason possible. Very few companies have that much money. Huntington Ingalls, for example, the biggest U.S. shipbuilder, has a market cap of $6-7B so a $2B acquisition would represent a massive fraction of the company. Among the big primes that would historically drive M&A in the defense space, Boeing is experiencing an existential moment, and Raytheon is still digesting its absorption of UTC. This leaves even fewer players on the field. Growth-stage, multi-billion-dollar firms with focus – especially if private equity is involved – represent much more likely M&A players than legacy primes with shaky balance sheets.

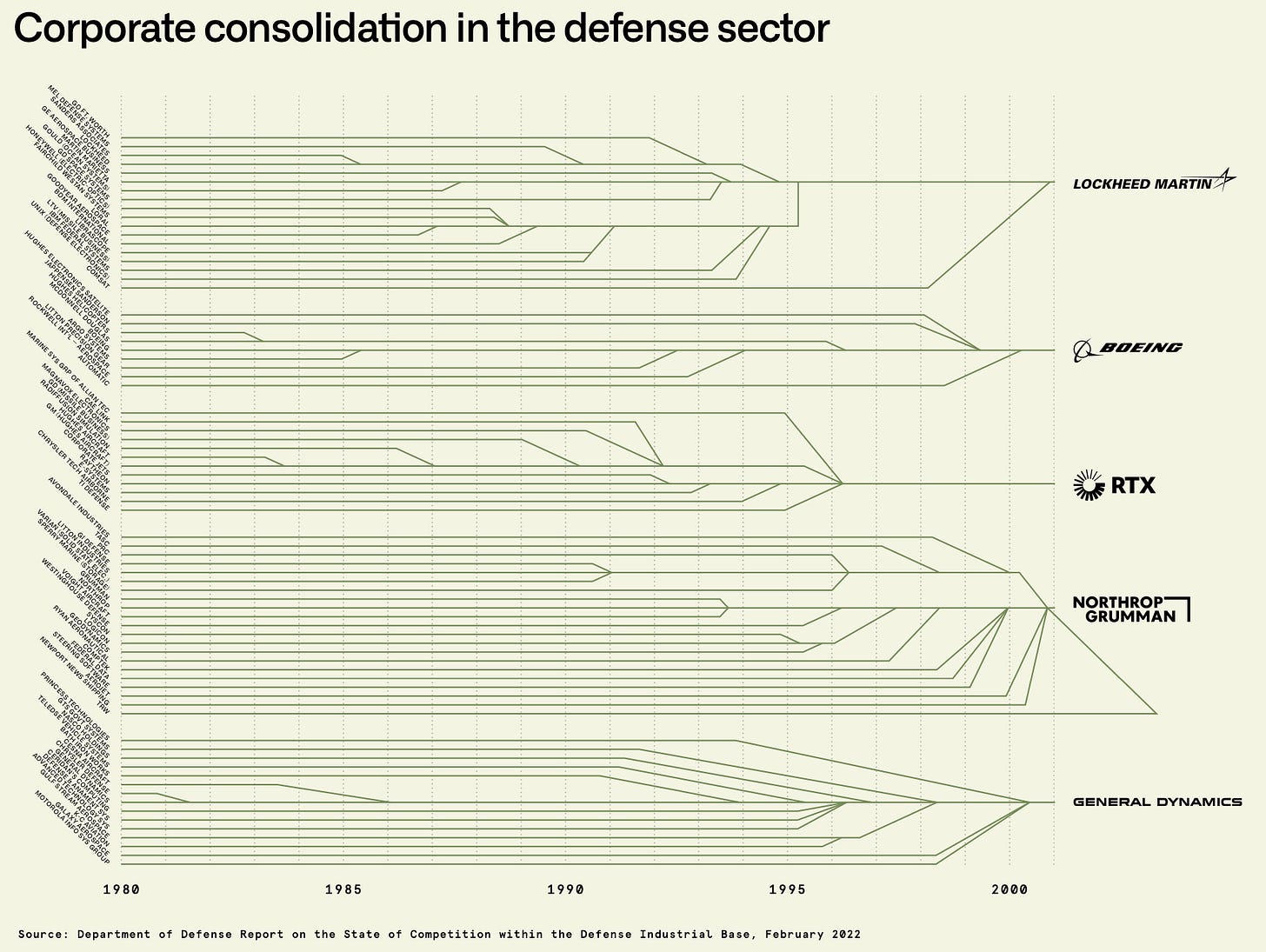

Time for the Deal-Flow Dinner

As the Pax Americana began with the end of the Cold War, the Secretary of Defense called major defense executives to the Pentagon for the infamous Last Supper. With President Clinton’s peace dividend, budgets would shrink, and their market would consolidate, he said. Since that 90s dinner, 51 leading defense companies have merged into 5. The resulting lack of competition – the Pentagon was always a monopsony buyer and post-Cold-War M&A shrunk most verticals to two suppliers of which only one was serious – has been well described by defense reformists.

Among others, Palantir CTO Shyam Sankar has articulated the case for a First Breakfast. Such an event would symbolize the arrival to open arms of many new competitors in the defense technology space. I’m here to tell you that the First Breakfast may be happening, but the time has also arrived for the Deal-Flow Dinner.

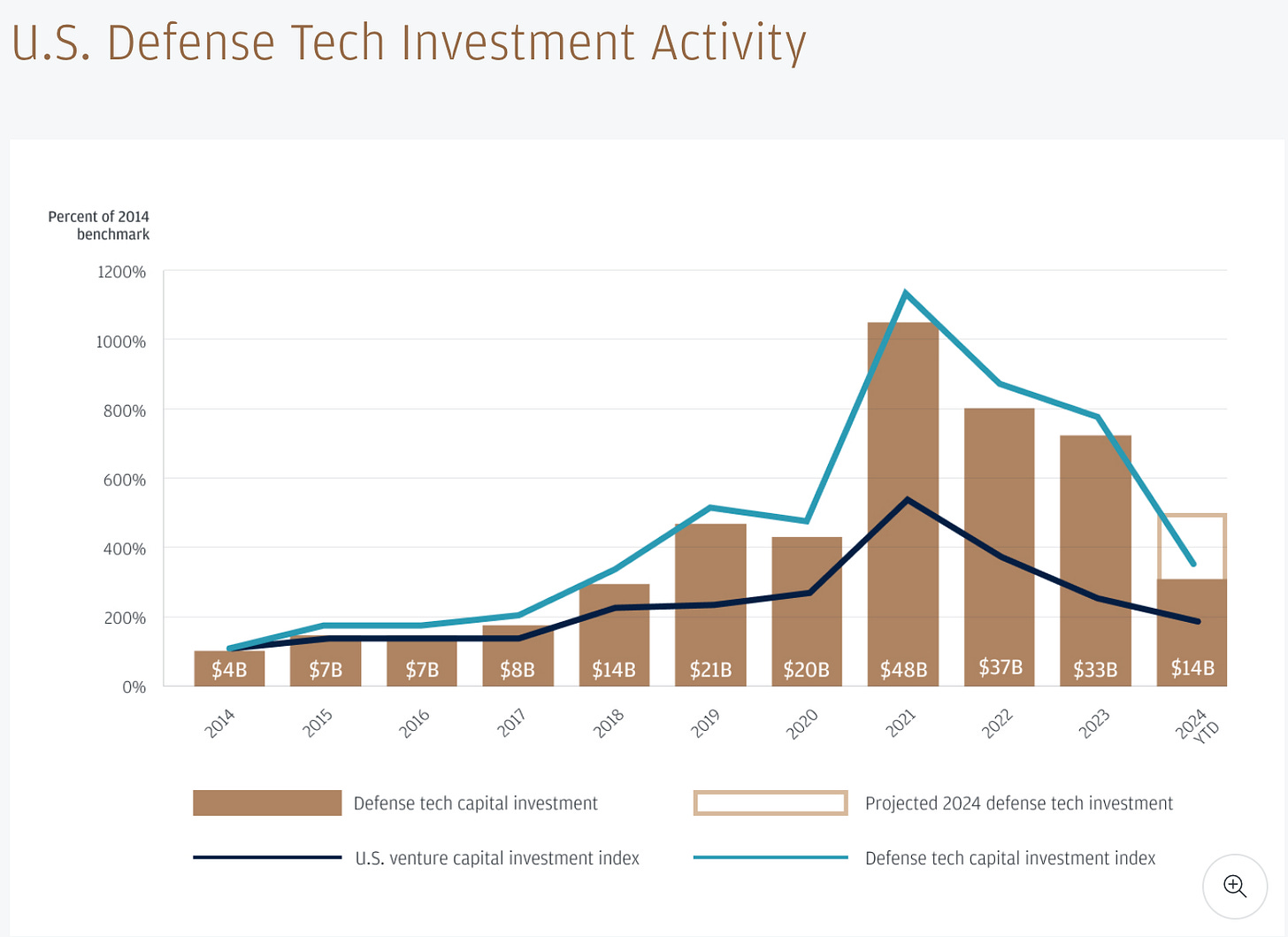

Although several VC-backed new entrants are growing, in hopes of becoming the next Palantir or Anduril, this takes time. Most of all, it takes the customer time to work through feedback, budget, and buy-in cycles, to scale new programs, and to turn more VC-backed tech companies into winners. The tech bros must move at pace with their customers. A simple rule of thumb is that the fastest sale cycle for a program of record-scale capability is five years – the valley of death is not narrow. Venture funds also expect returns to take years. We are inside the five year mark from the deluge of defense tech venture financing, which did not start in earnest until 2021.

The Pax Americana is over and the Chinese are moving out. Fortunately, market-makers are too, and they’re re-building democracy’s arsenal. One M&A deal at a time, competition is returning to the Pentagon’s vendor base. Most of the VC-backed cohort needs time to mature. While they do, I am hopeful about the potential of M&A from growth stage companies to build the new primes.

The new AeroVironment offers DoD capability across many domains. It takes deep exposure to the reality of Ukraine’s battlefield and applies those lessons to Blue Halo’s broad, and higher-tech portfolio, from sea to space. The new Redwire has turned two disciplined sector strongmen into a potential multi-domain menace. If its next acquisition is in ground or maritime autonomy, it would become more credible still.

These deals exemplify the new primes being built. They won’t look exactly like the old primes: GE-style conglomerates. They won’t have the dazzle or X following of VC-backed tech bros. They will have the balance sheets and focus to compete.

Across America, and hopefully across allied nations, defense executives are making deals over dinner. They know the 21st century’s great game between the US and China has catalyzed a smaller, but no less urgent, competition in their market. The deal flow dinner is not one dinner, with executives called to Washington to be toasted by an all-powerful mandarin. It is a casual conference-side chat between two CEOs after another long day on the road. It is a Patagonia-clad PE team, meeting a mid-western manufacturer’s executives over steak in Chicago. And it is a celebratory closing dinner, combining capability. At this last dinner, everything costs too much, especially the lawyers. It is many dinners, in many places, among many great builders.

Well said, Austin. I love the Tatte analogy. While I agree that defense startups need more time to mature, I think M&A should happen at earlier stages. It’s not an efficient use of capital or time for startups to build overhead that isn’t uniquely tied to their core product when they need to scale. By teaming up earlier, startups can accelerate their emerging technologies much faster to address the threats of today and tomorrow.

Great analysis as always. I’m interested to see the multiples these start ups get acquired for and what premium existing primes will be willing to pay. There are some heady valuations out there and I’m uncertain some of these companies will grow into them.