The sUSV Market: Small, Saturated... but Strategic

Small USVs can monitor and control maritime chokepoints at low cost and risk, but the market upside for the private sector to develop this capability is very limited

There’s no denying it – Admirals are amped about sea denial. They talked about it at the Surface Navy Symposium all last week. Specifically, they’ve realized that small unmanned surface vessels (USVs) are perfect for holding chokepoints, denying conventional warships maneuver in constrained bodies of water, and blocking amphibious assaults.

I’m here to tell you that it’s an incredible capability – but I’ll also tell you what the admirals won’t: it’s a tiny market.

Not only is it small, but it might already be saturated.

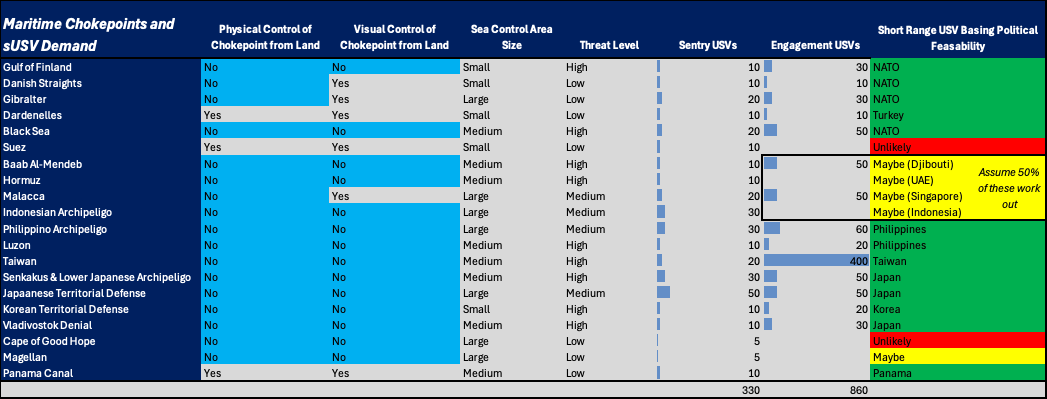

First, let’s analyze how many small USVs US and allied forces need to control critical chokepoints or deny them to Russian, Chinese, and other adversary forces. In the chart below, I’ve identified 20 critical maritime bodies of water. These are mainly the geographic chokepoints and Straits through which 90% of world trade flows, like the Suez Canal and Straits of Gibraltar. But they also include key military geography, like the Taiwan Strait, where US small USVs could deny the Russian or Chinese Navy maneuver.

If I missed any important maritime chokepoints, please drop a comment or send me a note - geography is cool!

A few categories of chokepoints:

Very Narrow Canals: To my knowledge, the Dardanelles, Suez Canal, and Panama Canal are physically controlled by the Turks, Egyptians, and Panamanians respectively. These bodies of water are so narrow that they can be physically blocked off from land. Historically, the Turks have drawn a physical chain across their Straits at Istanbul. Today, under the Montreux convention, they are barring new warships from entering, as long as the conflict continues between Ukraine and Russia. I’ve still allocated each of these Straits some USVs, but host countries don’t need them to deny passage.

Narrow Straits: The Straits of Malacca, Gibraltar, and the Danish Straits are also quite narrow. To my knowledge, they’re not narrow enough to easily block off, and they don’t need locks like a canal, but you can see across them easily. Since they’re this narrow, they can be defended with simple land-based weapons. USVs can help, but aren’t a game changer. I still think these bodies of water could use some USVs, but more for forward sentry work, and less to control the sea.

Critical Military Bodies of Water: The Taiwan Strait might be front of mind, but many such maritime chokepoints, what Navy intelligence calls Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) could use USVs, or be denied by their usage.

Unfortunately for the Russian Navy, most of their ports are based in small bodies of water. Russia’s Black Sea and Baltic Sea Fleets are stuck in small seas, each controlled by a NATO country chokepoint. Allied forces can block them in at the Danish Straits or Dardanelles. But they could also use expendable USVs to hammer the Russian Fleet in the Gulf of Finland, or any time it leaves port, as the Ukrainians have done in the Black Sea. Small USVs are so effective in the Black Sea that the Russian fleet has fallen back from their prized port of Sevastopol to the Russian mainland. The Russian North Sea Fleet is based in the White Sea, deep in the Arctic. It’s possible that Norway-based USVs could hit Russian Naval units leaving the White Sea, but I left the White Sea off this list because it’s far from NATO basing and very challenging to operate in that environment. The high north will be a later market for this tech. Russia’s Pacific Fleet at Vladivostok is a bit far from Japan, but isn’t out of range based on Black Sea operational data, and would deserve attention in a hot war.

One of the Chinese Communist Party’s great fears is containment. They saw how effective this strategy was in the Cold War against Russia. All up and down the first island chain – from the Straits of Malacca to the Philippino and Japanese archipelagos – are chokepoints and Straits that small USVs can monitor and cut off. No Strait looms as large as that separating Taiwan and China. The Replicator initiative has been buying USVs for Hellscape, Admiral Paparo’s sea denial plan to deter or defeat a Chinese amphibious invasion. The first island chain, with many chokepoints, is a great market for small USVs.

Commercial Shipping Lanes: The remaining chokepoints that small USVs can control are the major shipping lanes. Some of these, such as the Bab al Mandeb at the bottom of the Red Sea, have already become hot combat zones. A US fleet of USVs that could operate in the Southern Red Sea would surely be welcomed by fatigued surface sailors. When I attended a Red Sea combat brief recently, US USVs didn’t come up once, because the fighting fleet is still the manned fleet.

Further afield are critical lanes around the Panama Canal and the Southern Sea. These chokepoints are very important sources of maritime transportation, especially when other chokepoints become clogged in conflict.

When the Suez Canal was clogged by the Merchant Vessel Ever Given in 2021, I was there on the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower. We were trying to get from the Mediterranean to the Middle East to help cover the Afghanistan retreat – but the canal got clogged. On our admiral’s orders, we quickly calculated the time to circumnavigate Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope. We didn’t execute this course of action, but my takeaway was clear: all the maritime chokepoints matter, because we won’t always be able to count on the smaller, manmade ones.

How Many USVs To Control the Chokepoints?

First, it’s important to realize that there are two very different types of small USVs.

The first are the renewably powered vessels. In this category, companies like Saildrone, SeaSats, and OceanAero offer navies high endurance sensor deployment at very low cost. The main drawback: very low speed. Since batteries can’t hold enough energy to move USVs quickly for long periods of time, most of these USVs cruise at 2-3 knots and can sprint at 5 knots for short distances. They are great sentries.

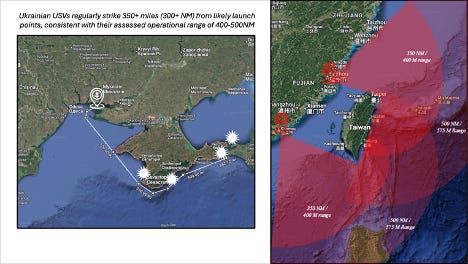

The second category are the speedboats. These are what Ukraine and the Houthis are using against much better equipped adversaries. They’re fast, tactical, and dangerous. But they have very limited range. Most only operate in the littorals and Ukrainian USV strikes have only been observed within an operational range of a few hundred miles. For more discussion on the range of small USVs, check out this analysis of China’s small USVs, which includes discussion of the map below overlaying Ukrainian operational USV range onto the Western Pacific theater.

For each chokepoint, I took a schwag at the number of speedboat USVs and the number of renewably powered USVs you might want to control it. For areas with hot combat potential, I allocated more speedboats – you might even consider using these up like ammo in the Ukrainian case. For areas with less hot combat, but bigger ocean areas to patrol, I allocated more renewably powered sentry USVs. For example, the Panama canal doesn’t need speedboats for control, but some low-priced SeaSats sentries could be spaced out in the Caribbean and in the Pacific to enhance map fidelity.

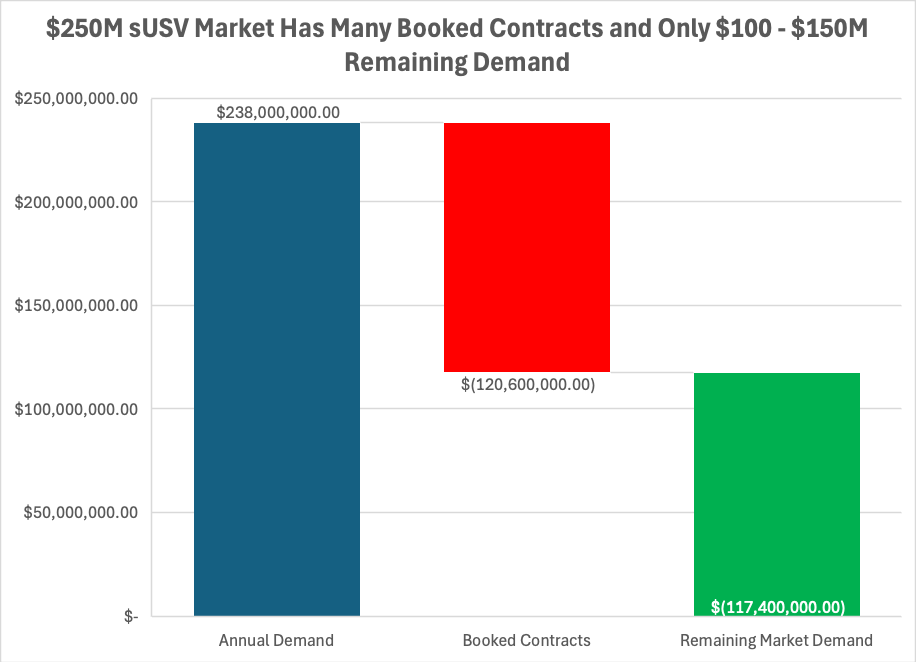

My numbers:

330 Renewably-Powered Sentries

860 Speedboat Interceptors

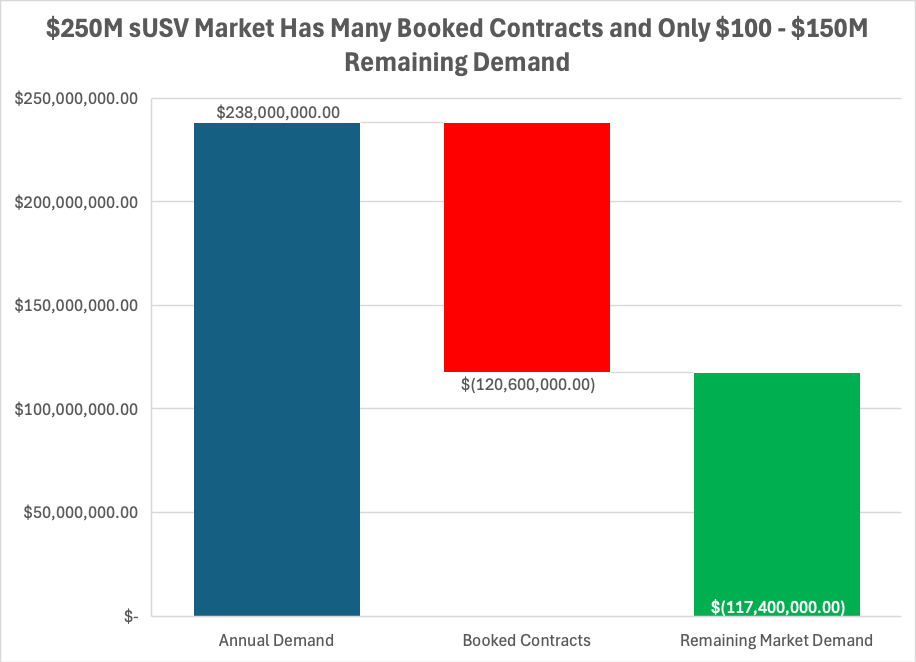

This is a lot of boats. But it’s a lot of boats, not ships. Let’s make a swinging assumption that the average price of these USVs is $1M. That makes it a $1.2B market. If they’re refreshed every 10 years, that’s an annual $120M market. Even if the vessels are refreshed every 5 years and the market is 2x my schwag ($2.4B) that’s a $480M annual market. I know that pricing for many of these USVs, including the companies getting a fair amount of DoD traction, ranges from $100-500k. Most of the Replicator USVs went for about $400k. So assuming $1M per USV is also very generous.

The market is small.

And saturated

The Navy hasn’t purchased USVs for all these sea denial missions, but we have some datapoints on how many orders the Navy has already placed.

MAPC, a portfolio company of BlackSea, has raised production for its USV up to 32 per month. This would be 384 per year, and suggests that it got the big Hellscape / Replicator / Taiwan Strait order. Black Sea is not a Venture-Capital-backed company that builds forward of demand, but a traditional defense contractor. So they’re on contract. For simplicity, I’ll assume MAPC’s 384 is the 400 for the Taiwan Strait mission. One last note on MAPC – they certainly didn’t spin up production to 32 per month only to stand it down in a year, so they may have a longer term contract for more USVs. However, Black Sea has been trying to sell MAPC for quite some time, and until I see a press release saying MAPC has been acquired, I’ll keep betting that Black Sea Technologies has been asking for too much money, because MAPC’s Replicator revenue is not real recurring revenue that drives strong Wall Street valuations. (Personally, I think Replicator and Ukraine revenue are bad ass, but the finance brethren disagree.)

Saronic, a VC-backed company, has raised $245 million and is supposedly raising $500 million more. Nothing is publicly available about their revenue or contracts, but I’ll take a wild swing and say they have at least $200M of contracts. This would value them at 15x their revenue – less than Anduril and Palantir, but incredible for a hardware-heavy company that bought a boat-yard. And this would mean they could have sold 200 $1M USVs. I’ve heard Saronic’s USVs are a bit more expensive, so maybe they’ve only sold 100 USVs. The Corsair, which they launched a few months ago, is their largest USV and would be the highest priced, but the contract bookings probably came in for one of the earlier products.

Havoc AI just raised $11M seed capital. Let’s assume they’ve sold at least 5 USVs.

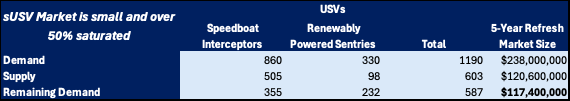

Speedboat Interceptor USVs:

Total Demand: 860

Contracts Booked: 400 + 100 + 5 = 505

Remaining Demand = 355 USVs

Saildrone has been around for quite some time. I know of multiple theaters and customers where they operate. They are primarily a commercial company, not defense, but I’ll schwag that they have 20 USVs operational with US forces, which might include some the US would re-allocate to critical sea-lanes, instead of current missions collecting weather data. They’re producing with Austal – a USV every 6 weeks. Over 5 years, that would be 43 additional USVs, assuming they have a production contract with the DoD. 63 USVs from Saildrone.

OceanAero has also been around for a bit. I know of multiple theaters where they’re operational, and more customers that have purchased the Triton for testing. This is probably 5x in 3 different theaters and another 15 in the water or on order. Total of 30 Tritons.

SeaSats is about to close another fundraising round, and like Havoc AI, I’ll assume they’ve also sold 5-10 USVs.

Renewably Powered Sentry USVs

Total Demand: 330

Contracts Booked: 63 + 30 + 5 = 98

Remaining Demand = 232 USVs

I’ll add that there are several other companies making very cool USVs in these categories. I don’t mean to dismiss them, but large government contracts or venture capital rounds are the best barometers for scale. Many larger companies are making sUSVs too. Metal Shark has an LRUSV program with the US Marine Corps and Textron has the CUSV program with the US Navy. Barriers to entry to make a small USV are quite low, so supply can easily meet demand, and innovative companies can rapidly drive the tech forward.

Regardless, this leaves 355+232 = 587 USVs of demand. Even if your USV only lasts five years before buying new ones (like keyboards) there would be $117M of annual remaining market demand. Even if the remaining USVs are higher capability, higher price, the market is small. Saronic is smart for going up market and building a higher end capability, because the market is too small to build a great business with the low end capability.

A market with $117M annual revenue to capture is not a big market.

Wall Street vs Naval Intelligence

I’m writing this piece because I’m worried that companies building great capability are going to have existential financial experiences in the coming years – years when we’ll need their capability.

If there is only a few hundred million dollars of demand left for small USVs, MAPC and Saronic could be the first to have trouble. MAPC could end up at a loss with their big 32 / month production line, and be forced into painful layoffs. Saronic has over 200 employees now, and will surely have more after raising another round. If the Navy isn’t buying hundreds of USVs from them per year, they’re going to struggle at some point to keep meeting investors’ expectations.

Saildrone too has a large team, lots of government affairs and defense sales salaries to justify, and probably needs to sell 20-50 USVs per year to operate sustainably.

Havoc and SeaSats, in different categories, need millions if not tens of millions in annual recurring revenue (e.g. selling 10s of USVs per year) in order to meet their valuations.

Defense revenue takes a long time to mature and grow. Anduril, despite incredible achievements, doesn’t yet have financial numbers pretty enough to trade publicly on Wall Street.

Some of these companies will likely be acquired by big primes during moments of financial distress. For DoD strategically, the capability should continue to exist. But the culture, the people, the entrepreneurial engine that churns out new and better product – that engine needs the catalyst of growth and the upside of a big market.

Great work on identification of market sizing! Wondering if expanding the use cases of sUSV's beyond just ASuW and ISR (sentry) would grow that market? Other uses cases for example: ASW, mine laying, mine countermeasures, AAW, undersea infrastructure protection etc. Also, non-military use cases e.g. Bathymetric and Hydrographic Surveys, subsea infrastructure inspection, Signature Measurement etc.

Good point Sean on attrition during wartime! Strike configured USV's could attrite like munitions.

There are a few additional chokepoints to the east of Malacca, Lombok and Sunda in the remainder of the Indonesian archipelago. Also: Torres Strait between Queensland and Papua New Guinea; in the Solomon Islands; the Southern Ocean including Bass Strait; Cook Strait connecting the Tasman Sea with the Pacific Ocean in New Zealand; Mozambique Channel; and all the straits and passes through the Philippine Islands connecting SCS with the Philippine Sea.