War has returned. As a boy in New York City on 9/11, I doodled depictions of German and Japanese bombers flying over Manhattan, dropping their weapons on our skyscrapers. The headmaster had descended to our quiet second grade homeroom – we had never seen him there, and never would again – and told us: “there was a bombing downtown.” We looked in awe back at him from our phalanx of desks, phonics workbooks still open. “We don’t know which of your parents are dead,” he said, informing us that the surviving parents would pick us up early. Then he moved on to the third grade homeroom. These were not his exact words, but our young minds inferred a clear message. The only imagery we knew of war and bombings came from movies: that legacy of World War Two with bold air raids mounted on enemy capitals and harbors.

That legacy has returned. But it has left the pages of history books and the hands of stick figures drawn in second grade classrooms. War is here. On most continents, destructive conflicts rage between powerful armies. Where they don’t, tensions brew. The Pax Americana has been over at least since the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War of 2020, if not since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014. This year alone, India and Pakistan reignited their long-simmering conflict, Israel and Iran finally escalated to full-scale war following decades of tension, and conflicts from Ukraine to Sudan to Myanmar worsened, often with little alarm internationally.

This piece will quickly argue – numbers and maps will demonstrate – that war is part of history, and it has returned. Then it will analyze implications across the countries most likely to partake in brewing melees.

Potential conflict analysis:

There are 10-20 simmering conflicts around the world you should pay attention to

Continent-by-continent analysis of major regional tension points, some of which you’ve never heard of

Defense industry implications:

Demand – How much % of GDP might be spent, where, on defense in this violent world?

Supply – Analysis of market and industrial implications

The conflicts we have seen around the world this year are serious. Worse, they suggest that countries are comfortable again settling their differences militarily. This realization is driving a global surge in arms spending – spending on armies, navies, and ever-more-deadly technology.

Uninvited but Inevitable: The Wars to Come

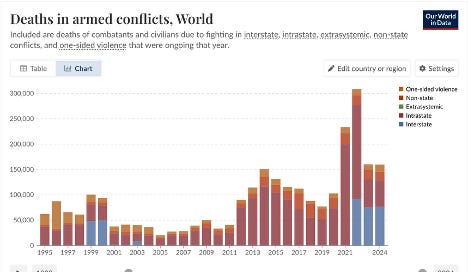

The chart below shows that interstate conflict has returned.

The 2000s – despite, or thanks to, Pentagon leaders whose favorite sound was the beating of war drums – was perhaps the most peaceful decade in history. America was at the height of her power. Although we invaded multiple countries in the Middle East, those conflicts were small in the scope of history. Since nation-states have organized relatively professional armies, serious wars are a regular feature. Recent peaceful decades are the exception.

They haven’t yet shown up in the stats, but 2025’s conflicts are much more violent and widespread than those of recent history. Ukraine-Russia casualties are driving the spike in interstate deaths in armed conflicts from two charts ago. Some more conservative counts have the combined death toll just under 100,000 per year, but others with broader definitions that include civilian casualties suggest Russia alone has already passed 1,000,000 casualties.

Initial reporting from the India-Pakistan conflict in May attributed only 200 total deaths to that exchange. However, posthumous decorations and funerals have revealed that Indian casualties were at least 250, belying previous Indian claims of zero casualties. Indian casualties include multiple elite Rafale pilots, suggesting India lost some of its most expensive and irreplaceable equipment too. Should Pakistan’s casualties equal India’s – they’re probably higher – the two sides would have been losing soldiers at a rate that would bring them to 45,000 deaths per year, a number only slightly below the equivalent Ukraine-Russia stat. Should Pakistan have twice as many casualties as India, the combined death rate would be closer to 70,000 per year.

The Israel-Iran battle – more of a one-sided Israeli dissection of Iranian targets – had many hundreds of deaths over just 12 days. Israeli bombardment would have killed 8-10,000 Iranian soldiers over the course of a year-long war, and many more civilians. Israel was likely not aiming to inflict casualties, but to degrade military, political, and economic targets.

The destructiveness of Israeli bombardment was far higher than the few hundred military casualties represented in the observable statistics. The same can be said for India-Pakistan tit-for-tat leveling each other’s military airfields. Ukraine and Russia have been bombing each other’s most critical energy infrastructure and military hardware with such ferocity that Ukraine last month set a record: the Operation Spiderweb strikes destroyed $7B of Russian equipment in a day. Wars with today’s destructive power can delete tens or hundreds of billions of value. If $7B of Russian equipment was destroyed every day, such destruction would easily delete more than the entire Russian GDP of that year.

Any of these conflicts alone would far surpass the most deadly conflicts of recent history. The vast civil wars in Myanmar and Sudan – in many ways they resemble conventional combat fought with mechanized maneuver, drones, and airstrikes – have killed hundreds of thousands in just a few years. Not even counted: the half a million children who have died of starvation in Sudan, or the 10+ million displaced people.

All these conflicts are happening concurrently, in split-screen, because the rules have changed.

At some point between the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine and the 2020 Azerbaijani surprise attack on Armenia – 2020’s isolation conditions may also have shown dictators hiding in their bunkers that they didn’t need the goodwill of democracies any more – war became conceivable enough that it started happening again.

Conflicts to Watch in a Brave, Dangerous World

Geopolitics this year has been punctuated by full-scale conflict in the Middle East, serious but short-lived conflict between India and Pakistan, and steadily growing tension between China and its smaller neighbors. Ukraine and Russia continue to grind and hack at each other’s forces.

In the background, many simmering disagreements between nation-states set conditions that could spark into armed conflict. Let’s move across the map, and look at some of the most concerning.

🌏 Asia

Most Post-Soviet States have border disputes, because their borders were drawn long ago by Muscovites. The Armenia-Azerbaijan war of 2020 showed that small states are willing to fight over such disputes, especially when security guarantees from the local hegemon fade. Russia-Ukraine shows that even the bigger powers can fight, and keep bearing once-unthinkable political and economic costs to wage war.

Fergana Valley (Kyrgyzstan – Tajikistan – Uzbekistan)

Why it matters: Soviet-era border complexity; water and land access.

Recent trends: 2021 Tajik–Kyrgyz clashes killed dozens; demarcation incomplete.

Assessment: 🔥 High risk. Border remains militarized, with recurring violence that could spark more conflict.

Kazakhstan–Russia (Caspian/Islet Border Tensions)

Why it matters: Caspian Sea resources; growing Kazakh nationalism.

Recent trends: Maritime incidents and rhetoric.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Potential hotspot amid Russia’s broader geopolitical pressure. Russia is currently quite distracted.

Georgia–Azerbaijan (David Gareja Monastery)

Why it matters: Religious and national symbolism.

Recent trends: Civil unrest and border patrol stand-offs.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Tensions inflamed by domestic politics. Azerbaijan’s military is combat-proven.

Japan-Russia (Kuril Islands)

Why it matters: Low probability, high impact because Japan and Russia are both massive

Recent trends: Nobody thinks this conflict will kick off, but it won’t go away either

Assessment: Low risk. If Russia gets even more distracted elsewhere, they deserve a surprise Japanese reclamation of the Kurils

In the Middle East, Iran and Israel’s full-scale war is what brought back the imagery of bombers over capitols to my brain. Israel will likely have to keep hitting Iranian sites and scientists in order to keep the nuclear program from regaining velocity. Yemen remains unstable, and at war with Israel. Syria and Lebanon have resolved the Asad years and the most recent war with Israel, but remain nearly-failed states. The only bright-spot in the region comes from the calming of Turkish-Kurdish tensions, which have stretched four decades and brought violence from Iraq and Syria to Turkey.

Iran’s weakness after a pummeling by Israel could re-spark its conflict with Pakistan from 2024 or that with Afghanistan from 2023. Alternatively, the UAE could use the moment to seize the strategic Strait of Hormuz islands it has long claimed, possibly with backing from international partners seeking to wrest the key international waterway from Iranian forces:

Abu Musa and Tunbs (UAE – Iran)

Why it matters: Strategic Strait of Hormuz islands.

Recent trends: UAE continues diplomatic claims; Iran maintains control.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Could be drawn into wider Gulf confrontation. Many of Iran’s neighbors could seize such an opportunity to resolve an old dispute.

In South and Southeast Asia, the civil war in Myanmar has left nearly 100,000 casualties and the central government in control of only 21% of the country. It shows no signs of receding, but more signs of recent Chinese involvement on both sides. Other tension-points persist across the region, any one of which could spark:

India–Nepal Border Disputes (Kalapani/Susta)

Why it matters: Colonial-era maps and nationalist politics.

Recent trends: 2020–21 saw maps revised and rhetoric rise.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Symbolic conflict could erupt under nationalist leadership.

Laos–Cambodia (Stung Treng / O’Tangav)

Why it matters: Undefined boundaries and resource access.

Recent trends: Local protests and minor border troop deployments.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Could escalate in regional power vacuum.

Last, and most significantly, the major conflicts involving Asia’s nuclear powers. India and Pakistan have hated each other since inception, and fought a violent, sharp war this year. Although they stopped, none of the root causes of that fight receded.

Why it matters: Nuclear powers with long-held grievance and repeated conflict

Recent trends: Pause of most recent 2025 war

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. No healing of the structural causes of this conflict

In East Asia, China has been ratcheting up pressure on Taiwan and the Philippines, pressing its long-held territorial disputes with its ever stronger naval forces. Although China has not fought a war for decades, it has a long history of disputes and violence with neighbors on land and sea, from Vietnam and Russia to India and Japan. The conflict over Taiwan, and potential U.S. involvement in it, will remain the most watched flashpoint on the global stage, with good reason.

Why it matters: Any Chinese expansionist conflict sets a precedent and threatens to bring in America and other global opponents

Recent trends: Ratcheting up pressure on neighbors with territorial disputes

Assessment: 🔥 High risk. Could escalate into full blown major power war

🌍 Africa

In North Africa, Libya remains broken and the Sahel (Mali, Niger, Chad, and Burkina-Faso) coup-prone and combustible. Morocco has several potential conflict points, with neighbors and its former colonial power Spain:

Western Sahara (Morocco – Polisario Front/Algeria)

Why it matters: Sovereignty dispute over a vast, resource-rich desert claimed by Morocco but partially controlled by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), supported by Algeria.

Recent trends: 2020 ceasefire collapse; drone strikes and skirmishes along the berm; rising diplomatic tensions following Israeli and U.S. recognition of Moroccan claims.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate to high risk. Renewed armed conflict is plausible if external pressure diminishes or Algeria–Morocco rivalry escalates.

Sudan has an ongoing civil war but also has border disputes with many neighbors. One of them could use Sudan’s internal weakness to resolve the border dispute. Alternatively, one of them could feel threatened by an unfriendly party gaining the upper hand inside Sudan, and join the fray.

Abyei & Heglig (Sudan – South Sudan)

Why it matters: Oil reserves and tribal allegiances. Abyei remains contested despite peace agreements.

Recent trends: UNISFA remains deployed, but regional instability worsens.

Assessment: 🔥 High risk. Proxy conflict between Sudanese and South Sudanese-aligned militias is increasingly plausible.

Ilemi Triangle (Kenya – South Sudan)

Why it matters: Pastoral access, border ambiguity.

Recent trends: Localized clashes; minimal state control.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Could evolve into state-level tension.

Hala’ib Triangle (Egypt – Sudan)

Why it matters: Maritime access and national prestige.

Recent trends: Sudanese internal instability; Egypt militarized.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Tensions rise as Sudan fractures further.

East Africa had a devastating two-year civil war in Ethiopia – hundreds of thousands of casualties and millions of displaced people – that culminated in the defeat of the Tigray rebels in 2022 by Ethiopian Federal and Eritrean forces. Although this conflict has been resolved, Eritrea and Ethiopia remain fragile. Red Sea states remain fragile with shifting conflict lines in Sudan and Yemen, and one flashpoint could sit between Eritrea and Djibouti. Of note, major outside powers from Russia to China to the U.S. seem willing to take risk to maintain Red Sea port access.

Doumeira Mountain (Eritrea – Djibouti)

Why it matters: Strategic position on Red Sea; Qatar peacekeepers withdrawn.

Recent trends: Eritrean troops remain; Djibouti on edge.

Assessment: 🔥 High risk. Lack of mediation could lead to accidental escalation.

In West Africa, Nigeria has seen ongoing civil war for years. Additional conflict between smaller states remains worth recognizing:

Koalou Triangle (Benin – Burkina Faso)

Why it matters: Border uncertainty and lack of civil registration.

Recent trends: Stateless populations, neutral zone governance.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Insecurity and lawlessness could attract external interest.

Kpéaba Village (Ivory Coast – Guinea)

Why it matters: Ethnic and border tension.

Recent trends: Incursions in 2016; unresolved tensions.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Local military activity could reignite instability.

🌎 North and South America

Although North America will likely remain stable, historic disputes should not be ignored. A cocky El Salvadorian government or a vulnerable Venezuelan one could lash out. Alternatively, Russian intelligence could help provoke conflict over resources or refugees, seeking to draw in and distract a Monroe-Doctrine-driven America.

Belize–Guatemala Dispute

Why it matters: Historic irredentism; territory covers southern half of Belize.

Recent trends: ICJ decision pending; military tensions have previously flared.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Outcome of ICJ ruling may catalyze unrest.

Conejo Island (El Salvador – Honduras)

Why it matters: Maritime control in Gulf of Fonseca.

Recent trends: Salvadoran nationalism rising under strongman governance.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Could erupt through naval posturing.

New River Triangle (Guyana – Suriname)

Why it matters: Border ambiguity; resource exploration.

Recent trends: Relative quiet, but underexplored jungle may hold strategic value.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Could flare if resource extraction begins.

French Guiana–Suriname (Maroni River)

Why it matters: Undefined river border; illegal mining and smuggling.

Recent trends: Cross-border tensions rising due to environmental and economic issues.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Weak state presence invites escalation.

🌍 Europe

In Europe, the Russian threat looms largest. With the Ukraine-Russia war only deepening, that conflict will remain at center stage. But Russia’s other neighbors expect probing and even full invasions once the Kremlin’s forces have reconstituted. When that time comes, they’ll be the most battle-hardened on the planet, backed by an industrial war machine no other nation has activated since the 1940s. Of all Russia’s neighbors, the Baltic nations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania remain the most uneasy about Russian re-armament.

Estonia–Russia (Ivangorod & Pechorsky District)

Why it matters: Treaty unratified; NATO-Russia fault line. One of several in the Baltics.

Recent trends: Russia withdrew from border treaty; Estonia citing 1920 treaty lines.

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. No imminent war, but long-term destabilizer.

Moldova–Russia (Transnistria)

Why it matters: Moldova is an EU and NATO frontier-state

Recent trends: Russia has been trying to de-stabilize Moldova and Transnistria even during the distraction of the Ukraine war

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. This is one area Russia could expand the front against NATO via proxy forces before a conflict in Ukraine ends. One thing that’s been on my mind for two years: why don’t the Ukrainians send a single brigade over to Transnistria for a few weeks to clear out the Russian rabble squatting there? This maneuver would shore up a flank and help NATO. MI6 and CIA should pay for this…

Greece–Turkey (Aegean maritime disputes)

Why it matters: Sovereignty, airspace, and energy exploration

Recent trends: Frequent military flights and maritime standoffs

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Possible flashpoint via accident or miscalculation. Turkey’s current leader often looks for external enemies to unify internally. Since he chilled out a bit about the Kurds, he may turn to the Greeks next

Croatia–Serbia Border (Danube Islands)

Why it matters: Post-Yugoslav disputes over water boundaries. One of several in the Balkans

Recent trends: No resolution; low-level disputes persist

Assessment: ⚠️ Moderate risk. Risk lies in nationalist politics or EU integration setbacks. This might be a good one for Russian GRU to try fanning

Defense Spending in the New Age

The twenty three conflicts above involve fifty countries. Most of these countries will not be dragged into wars. Most of the tension points will simmer, rather than spark. But today’s intense conflicts already show politicians and parliaments of the need for increased defense spending.

The last two years have seen sharp increases in defense spending already. Last month, the European members of NATO agreed to raise their defense spending target to 5% of GDP, a massive jump from today’s 2%. Such action would bring Europe’s combined defense budgets close to today’s trillion dollar American defense budget. Not wanting to miss out, the U.S. Congress sent a massive defense spending package to President Trump’s desk. Despite its size and ambition, many of the most powerful members of congress call it simply “inadequate.” They want more defense spending.

The 50 countries with flashpoints together account for 70% of the global economy. Let that sink in.

Between them, a 1.5% of GDP increase in defense spending would bring another trillion dollars of the global economy to defense spending, again as large as the Pentagon’s entire budget. For simplicity, at the end of this article is a table listing the countries and the approximate size of their economies and defense budgets. This count doesn’t even include many of the NATO countries who have already committed to massive military investments - because most NATO countries don’t have individual conflict risk, only collective via their Article 5 obligation.

Increased defense spending of this magnitude is probably tough for us to understand today. For our small community of defense tech builders, buyers, and shapers, a bigger defense budget sounds good for business. In a long-frozen, uncompetitive market, bigger budgets are what drive growth.

But humanity spending twice or thrice as much on weapons will not necessarily help us. Defense R&D will drive discoveries from aerospace to medicine, but an imbalanced, war-prone world will harm our species. Unfortunately, such a future seems inevitable, and only more painful if we do not prepare.

Five final takeaways and projections:

Defense spending in 2035 will be about one trillion dollars, or 1% of global GDP, higher than today

This projection accounts for relatively small increases from China, America, or Japan – massive economies and militaries

Even without great power war, serious state-on-state conflicts that can kill 50-100k people per year are not extinct. Three such examples have happened already in 2025

The true impact of these wars is much higher, and harder to quantify, in economic terms. And they leave many millions wounded, displaced, and starving

All of this is the new, risky reality of the post-pax world

Thank you.

All these conflicts have a common denominator;

None of them border the United States.

Nor do any of them threaten our maritime dominance.

The only power with means to seriously harm America is Russia, and their only motive our own reckless and feckless provocations on their borders and indeed proxy strikes into Russia itself.

Pax Americana has been an indulgence since 1989, since its become dangerous and expensive we should welcome its passing. All burden, no benefit. We need to rebuild and we will retrench.