All I Wanted For Christmas: Attritable Naval Platforms + A Force Architecture Continuum

Framing platforms as attritable is wrong. Instead, design forces to have sensor-shooter coverage across an expendable-survivable spectrum.

Inside Russian artillery range, I noticed something immediately: everything seemed attritable.

Platforms, people, and potential targets were not worth shooting at. On closer inspection, those worth hitting survived by concealing or toughening themselves. I framed this attritable-survivable dichotomy in Lessons from an Intelligence Officer on Ukraine’s Front Line.

But I was wrong.

I thought it looked like this:

But really it looked like this:

This piece will look at attritable platforms through two force architecture frameworks. First, we’ll look at the simple survivable-attritable dichotomy I understood from the line. We’ll find flaws. So we’ll move to a more sophisticated spectrum that captures today’s rapidly disaggregating platform-payload and sensor-shooter architectures.

Flawed Dichotomy

Attritable

Survivable

Better Spectrum

Expendable

Attritable

Risk Worthy

Survivable

Deep dives & applied analysis include:

Infantry and surface ships: problems on the attritable-survivable dichotomy

Are expensive drones still relevant?

Definitions on the spectrum: re-use, human crew, and platform economics

Russian aircraft example: a SU-35 attacks

Naval architecture and vertical launch (VLS) tubes: making ships too expensive

Carrier strike groups and attritable naval platforms: a gap

Trench warfare and the ground game: two systems locked in an eternal grind

The Flawed Attritable-Survivable Dichotomy

Much has been written about attritable platforms. Here is what I realized from the Donbas:

Survivable-Attritable Dichotomy

· Assume that, once targeted, units stay relevant only if they are survivable or attritable

· Evaluate U.S. Navy [or joint] force structure through this lens, scrapping platforms that are neither, or sending them to secondary theaters

· Proliferate expendable platforms throughout the fleet

The main takeaway that holds: anything in range and worth hitting will become irrelevant if it can’t defend itself or evade targeting.

To understand where it breaks down, I’ll use the chart below. It shows attritable assets on the bottom left and survivable assets on the top right. On the bottom right, it shows some expensive systems that aren’t stealthy or tough enough to risk on the battlefield.

First, I defined the axes by attritability. Blue forces don’t like losing expensive systems, but don’t mind losing cheap ones, so cheap-expensive is the X axis. Red forces, on the other hand, can think about the cost of what they’re shooting at, but first have to get a targeting solution, get past defenses, and expend finite strike resources. So I used a more abstract Y axis that gives the adversary a vote: difficulty to target and destroy.

These axes together show the cost-benefit ratio of hitting a platform

Attritable Example – Drones

Drones, such as UAS and USVs, are very cheap. They’re pretty easy to destroy, but you’ll want cheap ammo.

Dead Example – Expensive Drones

For decades, the US relied on expensive drones such as the Predator and Reaper to patrol and strike terrorist targets across vast distances. This was a low risk way to keep NATO boots off of Middle Eastern ground, but with surface-to-air missiles proliferating and the Pax Americana over, these expensive drones don’t have enough stealth or toughness for combat zones. The headline below from 2019 reminded me that shoot-down of these exquisite systems remained rare during the peace.

But the peace is over. This year alone, 10x MQ-9 Reapers have been shot down.

Survivable Example – Submarines

Submarines are the ultimate survivable assets. At this point, they’re expensive and important enough that militaries will keep spending to ensure they stay stealthy, and survivable.

Two Problems – Infantry and Surface Ships

Infantry show up in several forms

Penal infantry, as the Russians use them, are quite expendable.

Dispersed infantry, the most common form, are better trained and harder to hit. They make up most of the front line. Since you expect to lose them every day, they’re attritable. Not all infantry are attritable though.

Massed infantry is in the bottom right quadrant. Ukrainians and Russians have stopped massing infantry because doing so brings death.

SOF (Special Operations Forces) are rare and expensive to train, but stealthy enough to keep their attrition low, so they’re in the top right, survivable.

So it depends how you use the infantry. Russian infantry are more attritable than Ukrainian because of demographics and their political system.

Surface vessels are also all over the map

Small Uncrewed Surface Vessels (USVs), like Ukrainian or Houthi speedboats, are certainly attritable – they cost only tens or hundreds of thousands and are built for suicide missions

The Russian Black Sea fleet, much of which has been destroyed over the past two years, is dead, in the bottom right corner.

Except for logistics vessels, which are very expensive and have no defenses or stealth, the US Navy’s fleet of ships should be survivable.

I write should with the utmost delicacy: should their counter-targeting and air defenses hold. US Navy air defenses have held up well in the Red Sea, where they’ve faced ever more complex drone and missile attacks. But the PLA has so much ammo, production capacity, and long-range strike optionality that US ships can only be so survivable.

The PLARF (PLA Rocket Force) can shoot 20x $10M ballistic missiles ($200M) at each US Destroyer ($2B) and break even if only 1 in 200 missiles gets through. If 5 of 200 get through, they could sink $10B worth of Navy assets, two years of shipbuilding capacity, and thousands of US Sailors. The missiles are expendable. The ships are not survivable.

Infantry and ships show that it depends. If a soldier can be attritable, survivable, or dead depending on his training, where he is on the map, what other units support him – then we don’t really know what he is or how to use him.

If ships with air defenses get to be called survivable, they’ll only stay survivable if they fight in ways conducive to their defensive strength. US Military Sealift Command oilers are such obvious targets that they can only be employed survivably, i.e. out of range or with convoy.

The attritable-survivable dichotomy can capture how platforms are being used, but fails to offer a compelling vision of how platforms should be used and how the force should be designed.

The Spectrum: Expendable – Attritable – Risk Worthy – Survivable

Kill Chain punched the concept of platform-centric warfighting in the face like Mike Tyson. Years before Ukraine or Azerbaijan, Brose pointed out that modern computers and wireless communications meant that war-winning force design would build distributed webs of capability. The next great war would be fought between systems of systems.

When Ukraine happened, simple brains like mine jumped back to platforms. Drones were in. Logistics ships were out. Russian ships were on the bottom.

But trench warfare was back in too. Patriot missile defenses helped Ukraine immensely, but increasing Russian air attack complexity started getting through quite quickly. Attrition warfare came roaring back, proving Kill Chain right, it was a battle between systems of systems.

Attritable platforms don’t matter

Survivable platforms don’t matter.

The system of platforms, the force architecture, the distribution of payloads across the battlefield: these matter. Decades ago, Soviet generals coined the term “reconnaissance-strike complex.” This framework showed the building blocks of modern militaries to be shooters, sensors, and networks to connect the two. Since sensors and shooters usually reside on platforms, let us enter a simple world where all battlefield tech is either a platform or a payload.

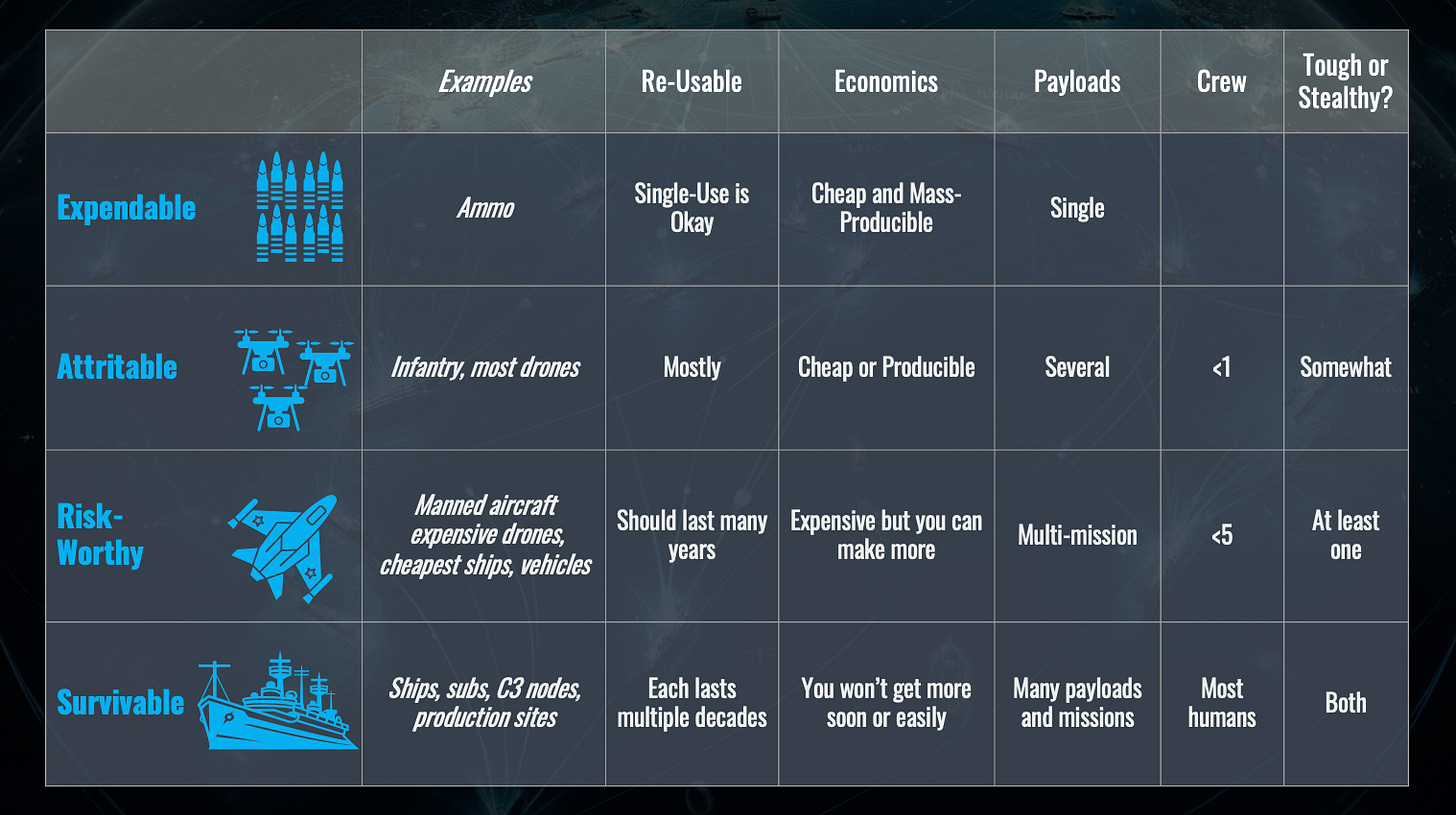

In order to carry sensors and shooters close to the adversary, forces need many different platforms, ranging from cheap and expendable to exquisite and survivable. Institute of the Study of War explains the expendable-survivable continuum nicely:

The cost curve of the offense-defense race in the air has become a factor in systems design. The scarcity, expense, and difficulty of mass-producing high-end interceptors has forced Ukraine (and Israel) to design IAMDs that can allocate the cheapest and most available defense systems against targets they can destroy while preserving the rarest and most expensive systems for the hardest threats—and to adjust prioritization and integration dynamically as the character of attacks changes. Sometimes important innovations come from using the most mundane technologies—Ukraine lifted the burden of shooting down many drones from expensive systems by fielding mobile fire teams equipped with shotguns and rifles, for example.

Because our brains (and acquisition systems) still focus on platforms, we can categorize platforms, based on their position on this cost-capability curve. I argue that we should consider all platforms as expendable, attritable, risk-worthy, or survivable. More, effective force design calls for expendable, attritable, risk-worthy, and survivable platforms in air, land, and sea domains. Within a force, ammo might be single use and expendable, and aircraft carriers might only be used surivably, but most platforms can be used survivably, with risk, or attritably. Without platforms spread along the cost-risk curve, your adversary will find weak points and create favorable matchups.

Some attempts at definitions:

Russian Aircraft Example: Because of their range and speed, aircraft can be used against every type of adversary, so they show us a lot about force design and utilization.

Survivable: A Russian SU-35 striking Ukrainian infantry from behind Russian lines is being used survivably

Risk-Worthy: A Russian SU-35 engaging Ukrainian F-16s or dipping in and out of Ukrainian air defense range is being risked, but not attrited

Attritable: A Russian SU-35 squadron conducting a strike deep into Ukrainian territory, against good air defenses, should expect some attrition

Expendable: Even expensive fighter-bombers could be used expendably, but this would be unwise. Why do so, when you can expend missiles and long-range suicide UAVs?

Since the Russian commander can use his SU-35 in many ways, he should use it where the matchup is favorable. On today’s battlefield, commanders treat crewed aircraft like SU-35 as survivable and risk-worthy >95% of the time. They probably sign off on some attritable use-cases too, such as for high-value targets where missiles alone will struggle to penetrate. For many targets though, they can achieve the same effect at much lower risk with a missile or drone.

Sea-Air Force Architecture > Naval Architecture

The US carrier strike group presents the perfect example through which to analyze not just a platform, but a system of platforms. Carriers need to be survivable. In WW2 we could build more carriers, so I’d argue we often used them in a risk-worthy manner, such as in major campaign offensives.

Today, to keep carriers alive, you need surface combatants with air defense ammo. This assumption, as Cruisers have retired with their many VLS (Vertical Launch System) missile cells, has driven requirements for Frigates ($1B+) and Large USVs ($300M+) to have many VLS cells. The force wants missile defenses for the carrier.

Magazine anxiety has made Frigate and LUSV more complex and both programs have spiraled into expensive tennis matches between requirements officers and naval architects, with each side returning a heavier, more capable, more expensive ship that the US industrial base is worse at building. FFG is a cluster. LUSV is at at risk.

Basing a fleet architecture on expensive ships poses two problems. First, crewed ships are so expensive they can only be used survivably. Second, their primary weapon system is a single use, expensive missile

Fleets based on VLS create lopsided force architectures. They don’t cover the attritable and expendable portions of the cost-curve, except with expensive missiles.

Fortunately, the rest of the carrier strike group helps balance the lopsided surface fleet. Working out from the destroyer, what’s next? Manned aircraft like F-18s and F-35s, with range, speed, and some survivability: these seem risk-worthy. They can go further from the carrier, a few can be lost, but they cannot be attrited in great numbers unless they are trading themselves for adversary ships.

With destroyers, carriers, and aircraft counted, what remains in the carrier strike group? The ammo? Missiles, we’ve already covered, are quite precious. They’re not mass-producible, they’re expensive, and we must save them to counter the adversary’s arsenal. But missiles are single use. Single use weapons, even expensive ones, must have expendable use cases.

The only cheap platforms fielded in any numbers, with the range to move on the open ocean, are renewably powered USVs. Although there isn’t any public evidence they’re integrated with Big Navy Carrier Strike Group operations, solar- and wind-powered USVs offer the Navy attritable and expendable sensors on the surface. They range from expensive Saildrones to cheaper SeaSats, or even bouys.

A note on small USVs. Small USVs are great. They’ve hammered Russia’s Navy for two years and started causing problems for the US Navy in the Middle East. But they can’t keep up with the surface fleet. There is no room on destroyers for more speedboats – try asking a DDG skipper if they’ll give up one of their RIBs for a small USV. If you find one that crazy, help them launch and recover a speedboat USV in Sea State 4 for a few hours on a cold morning and see if they still want the tech.

In order to create risk-acceptable matchups, carrier strike group commanders need air assets of many different costs to carry sensors and some shooters. Many of these would be attritable and risk-worthy ISR UAS - long-range would drive cost up. Expendable sensor drones and one-way-attack UAS would help too.

On the surface, the Navy needs to deploy, operationalize, and scale renewably-powered USVs that can sew the ocean with expendable and attritable low cost sensors. Additionally, they need lower cost shooters sitting on the surface, closer to the adversary, probably in the form of attritable and risk-worthy USVs with some serious range.

The Navy has payloads to shoot and sense at many costs and ranges. Now they just need platforms to deploy these at acceptable risk. Surface platforms must use their long dwell time and buoyancy to disaggregate heavy shooting and sensing payloads on the water alongside destroyers.

An attritable naval platform is surely coming. It’s all I wanted for Christmas. I bet I wasn’t alone.

The Ground Game – Locked in an Eternal Struggle

Fighting from frozen tunnels and trenches, Russian soldiers test Ukraine’s lattice of sensors across the no man’s land. They send drones to probe or peck away, revealing what the adversary can see and hit. Where they find weakness, they push. Where they find exposed hardware, they hit. And where they find favorable matchups, they take risks.

The two armies are locked in systemic struggle with millions of sensors, shooters, and platforms facing off. The Russian meat grinder works because their force can expend infantry and drones, attrite better trained infantry and vehicles, and risk aerial assets to support an assault. The Ukrainian lines hold by expending drones, attriting infantry, and risking additional forces on attacks that spread the adversary across the line and degrade force generation.

Both sides have options at every step on the expendable-survivable continuum.

Bonus, here’s me on a US-donated vehicle too nice to be attritable. The Humvee is an obvious, expensive target. So this unit kept it behind the line and used it survivably. On the line, they employ cheap, used pickups they can afford to attrite. When we took this photo, they were probably saving the Humvee for an assault where they would need its extra protection.